What do the workings of red blood cells, ensuring breathable air for astronauts, and scraping soil off NASA’s Viking spacecraft have in common? The sharp thinking of biochemist Emmett Chappelle.

February is Black History Month in the US—a time to reflect on the contributions of African Americans in all fields and celebrate their accomplishments while recognizing the adversity they had to overcome in American society.

2021 also marks 30 years since the first firefly luciferase reporter vectors and detection reagents became available as products. There’s no better person to highlight this month than Emmett Chappelle, whose work with the luciferase reaction is still used for many applications today.

Chappelle gained recognition for his original research into iron recycling by red blood cells and anaphylactic shock when he served as an instructor at Meharry Medical College in the early 1950s. This recognition resulted in his attendance at the University of Washington to complete an M.S. in Biology. After receiving his masters, Chappelle pursued graduate work toward a PhD before taking a research position at the Research Institute for Advanced Studies in Baltimore, Maryland. His work on plant health and photosynthesis helped ensure breathable air for astronauts.

Chappelle next joined the staff at NASA as an exobiologist working on the Viking spacecraft missions. His goal was to find a way to detect living microbes in extraterrestrial soil samples. To do that, he co-opted the luciferase reaction.

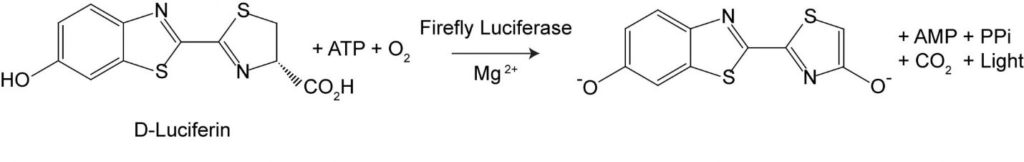

Luciferase is an enzyme that catalyzes (speeds up) a reaction involving luciferin, ATP (adenosine triphosphate), magnesium and oxygen. The chemical reaction itself involves two steps. First, in the presence of luciferase, luciferin reacts with ATP make luciferyl adenylate and ADP. The next step involves the luciferyl adenylate reacting with oxygen to change into oxyluciferin, as well as producing AMP (adenosine monophosphate) and light. The key to Chappelle’s work is the role of ATP.

ATP is the energy “currency” of organisms and is present in every living organism. ATP is also degraded rapidly upon cell death. So, if you can detect ATP in any kind of sample, you can be very certain there is at least one living cell in that sample. His discovery resulted in his applying for and receiving a series of patents, the earliest of which described a “method of detecting and counting bacteria” in which bacterial ATP is released by cell rupture and is measured by an enzymatic bioluminescent assay. Basically, the system is supplied with everything needed to drive the light-producing bioluminescent reaction except ATP. Light will only be detected if there is ATP in the sample, and the ATP can only come from living organisms.

This strategy is similar to those used today to monitor facility and drinking water quality and in pharmaceutical research and development. In fact, it is still used today to evaluate extraterrestrial samples for signs of life as we know it.

As new luciferase proteins are engineered and substrates improved, this reaction that lights up the natural world will also continue to light up the answers that scientists seek today. It is Emmett Chappelle’s insight into the possibilities of this chemical reaction that has made these new discoveries possible.

Sources and Further Reading

- Gentry, D.M. et al. (2017) Correlations between life-detection techniques and implications for sampling site selectin in planetary analog missions. Astrobiology 17, 1009–1021.

- Patents by Inventor Emmett W. Chappelle. Justia Patents https://patents.justia.com/inventor/emmett-w-chappelle

- Archives. (1975) Fireflies’ Light Gains New Uses in Medical and Technical Research. The New York Times

- Bellis, Mary. (2019) Biography of Emmett Chappelle, American Inventor.

Michele Arduengo

Latest posts by Michele Arduengo (see all)

- An Unexpected Role for RNA Methylation in Mitosis Leads to New Understanding of Neurodevelopmental Disorders - March 27, 2025

- Unlocking the Secrets of ADP-Ribosylation with Arg-C Ultra Protease, a Key Enzyme for Studying Ester-Linked Protein Modifications - November 13, 2024

- Exploring the Respiratory Virus Landscape: Pre-Pandemic Data and Pandemic Preparedness - October 29, 2024