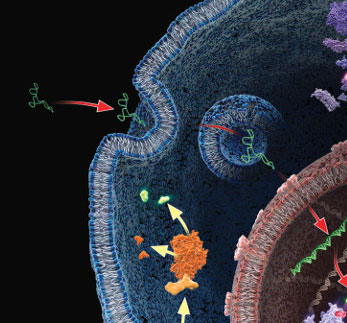

When looking at small aspects of living things, especially cells, it can often be difficult to fully grasp the magnitude of regulation employed within them. We first learn the central dogma in high school biology. This is the core concept that DNA makes RNA and RNA makes protein. Despite this early education, it can be lost on many the biological methods that are employed to regulate this process. This regulation is very important when one considers the disastrous things that can occur when this process goes askew, such as cancer, or dysregulated cell death. Therefor it is very important to understand how these regulatory mechanisms work and employ tools to better understand them.

Continue reading “Small RNA Transfection: How Small Players Can Make a Big Impact”

This review is a guest blog by Amy Landreman, Product Specialist in Cellular Analysis at Promega Corporation.

This review is a guest blog by Amy Landreman, Product Specialist in Cellular Analysis at Promega Corporation.