The first time I performed PCR was in 1992. I was finishing my Bachelors in Genetics and had an independent study project in a population genetics laboratory. My task was to try using a new technique, RAPD PCR, to distinguish clonal populations of the sea anemone, Metridium senile. These creatures can reproduce both sexually and asexually, which can make population genetics studies challenging. My professor was looking for a relatively simple method to identify individuals who were genetically identical (i.e., potential clones).

The first time I performed PCR was in 1992. I was finishing my Bachelors in Genetics and had an independent study project in a population genetics laboratory. My task was to try using a new technique, RAPD PCR, to distinguish clonal populations of the sea anemone, Metridium senile. These creatures can reproduce both sexually and asexually, which can make population genetics studies challenging. My professor was looking for a relatively simple method to identify individuals who were genetically identical (i.e., potential clones).

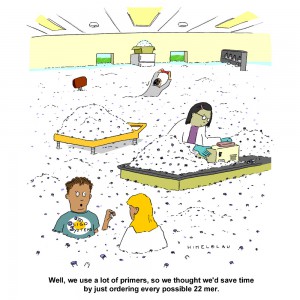

PCR was still in its infancy. No one in my lab had ever tried it before, and the department had one thermal cycler, which was located in a building across the street. We had a paper describing RAPD PCR for population work, so we ordered primers and Taq DNA polymerase and set about grinding up bits of frozen sea anemone to isolate the DNA. [The grinding process had to be done using a mortar and pestle seated in a bath of liquid nitrogen because the tissue had to remain frozen. If it thawed it became a disgusting mass of goo that was useless—but that is a topic for a different blog.] Since I had never done any of the procedures before, my professor and I assembled the first set of reactions together. When we ran our results on a gel, we had all sorts of bands—just what he was hoping to see. Unfortunately, we realized that we had added 10X more Taq DNA polymerase than we should have used. I repeated the amplification with the correct amount of Taq polymerase, and I saw nothing. Continue reading “Optimizing PCR: One Scientist’s Not So Fond Memories”