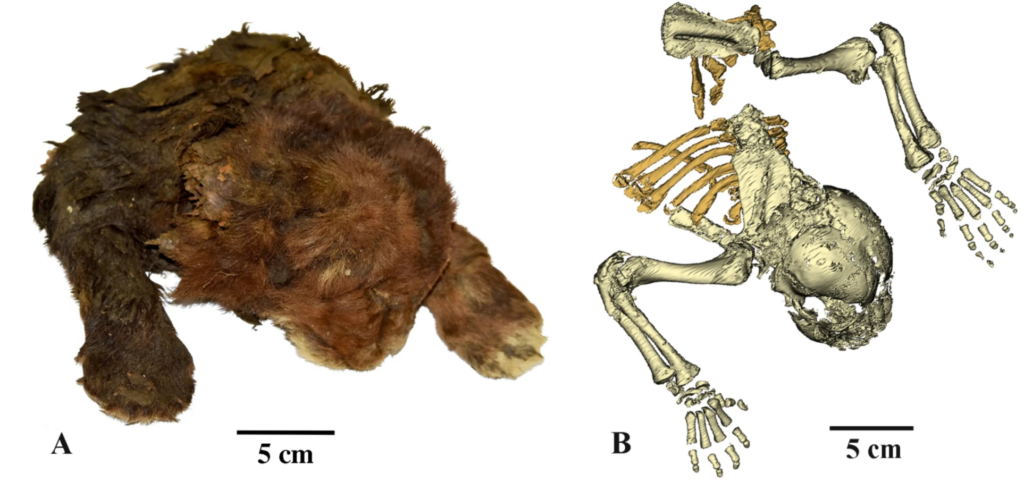

In the permafrost of Siberia, a remarkable discovery has been made—a mummified juvenile sabretooth cat, Homotherium latidens, frozen in time for over 35,000 years. This discovery, made along the Badyarikha River in the Indigirka River Basin of Yakutia, Russia, offers an exciting glimpse into a species that has no modern analog (a living equivalent of something extinct) (1). For paleontologists and evolutionary biologists, it provides an unprecedented look at an ancient predator that roamed the Earth during the Ice Age. So, how is this cub mummy truly fascinating scientists?

A Rare Find

The permafrost of Siberia is a treasure trove of Ice Age fossils, but the discovery of a mummified Homotherium cub stands out for its rarity and significance. While bones can tell us a lot about the history of an extinct species, mummies—where the animal’s soft tissues, such as fur, skin and sometimes internal organs, are preserved—offer far more detailed information. ‘Mummies’ refer to animals (or humans) that have been preserved with their soft tissues intact, often through natural or intentional processes like drying or embalming. This preservation allows scientists to gain insights into the organism’s diet, health, development and adaptations—details that bones alone can’t reveal!

Continue reading “Ice Age Secrets: The Discovery of a Juvenile Sabretooth Cat Mummy “

I am fascinated by all the ways that scientists are taking sensitive techniques and using them to look into our past. For example,

I am fascinated by all the ways that scientists are taking sensitive techniques and using them to look into our past. For example,