September 11, 2001 is the day that will live in infamy for my generation. On that beautiful late summer day, I was at my desk working on the Fall issue of Neural Notes magazine when a colleague learned of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center. As the morning wore on, we learned quickly that it wasn’t just one plane, and it wasn’t just the World Trade Center.

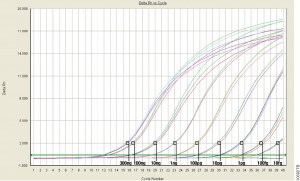

Information was sparse. The world wide web was incredibly slow, and social media wasn’t much of a thing—nothing more than a few listservs for the life sciences. Someone managed to find a TV with a rabbit-eared, foil-covered antenna, and we gathered in the cafeteria of Promega headquarters—our shock growing as more footage became available. At Promega, conversation immediately turned to how we could bring our DNA forensic analysis expertise to help and support the authorities with the identification of victims and cataloguing of reference samples.

Just as the internet and social media have evolved into faster and more powerful means of communication—no longer do we rely on TVs with antennas for breaking news—the technology that is used to identify victims of a tragedy from partial remains like bone fragments and teeth has also evolved to be faster and more powerful.

Teeth and Bones: Then and Now

“Bones tell me the story of a person’s life—how old they were, what their gender was, their ancestral background.” Kathy Reichs

Many stories, both fact and fiction, start with a discovery of bones from a burial site or other scene. Bones can be recovered from harsh environments, having been exposed to extreme heat, time, acidic soils, swamps, chemicals, animal activities, water, or fires and explosions. These exposures degrade the sample and make recovering DNA from the cells deep within the bone matrix difficult.

Continue reading “The Stories in the Bones: DNA Forensic Analysis 20 Years after 9/11”