In March 2016, two hikers on a trail east of Seattle, WA, found a little brown bat lying on the ground in obviously poor condition. The bat was taken to an animal shelter where it died two days later from White-Nose Syndrome (WNS).

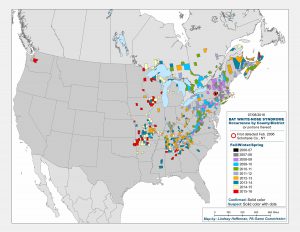

This bat was the first case of WNS found west of the Rocky Mountains. It represented a jump in the spread of WNS, and a troubling one. WNS was first detected in a cave in Albany, New York, and since then it has been moving slowly westward at a rate of about 200 miles per year, according to David Blehert of the United States Geological Survey, the laboratory that confirmed the WNS diagnosis for the Washington bat. Before this year’s discovery outside of Seattle, the westward-most case detected was in eastern Nebraska.

WNS, caused by a cold-loving fungus, Psuedogymnoascus destructans (Pd), can kill 100% of the hibernating bats in a colony, and in the ten years since it has been detected and monitored has killed over 6 million bats in the United States and Canada. As of July 2016, bats infected with the fungus have been found in 29 states and 5 Canadian provinces.

According to Blehert, this is probably the “most significant epizootic of wildlife” ever observed; never before have we seen hibernating mammals specifically affected by a skin fungus. What does that mean? Are we looking at extinction for some bat species? What are the ecological consequences of rapidly losing so many individuals to disease so quickly? And, what, if anything, can be done to combat the disease and help bat populations recover?

Continue reading “An Epizootic for the Ages: Revisiting the White-Nose Syndrome Story”