Oceanographer Robert Ballard’s literary showpiece The Discovery Of The Titanic today sits on a shelf in my bedroom collecting dust. Gone are the days when it was heavily leafed through by relatives and close friends mesmerized as they were by the glossy pictures and personal accounts of disaster contained within its covers. I had dismissed from mind images of the Titanic’s Captain Edward Smith and Marconi wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride that accompany the chilling story of the fateful night. I had forgotten about Ballard’s detailed chronicling of the turbulent expeditions that led to the eventual finding of the Titanic more than 70 years later. And I had put aside my fascination for the flagship submersible Argo that in 1985 had scoured the Atlantic at 13,000 feet below sea level until it finally met up with the eerie wreck of the luxury liner. But my interest in the book has recently been revived by the molecular characterization of a fastidious strain of bacteria that is “speeding up the decay of the historic wreck” (1).

When Ballard wrote his book over 25 years ago, biologists had already advanced the idea that micro-organisms were breaking down the iron cladding of the Titanic. His description of some of the first shuddersome glimpses of the ship’s contours give us an inkling of what was known at the time:

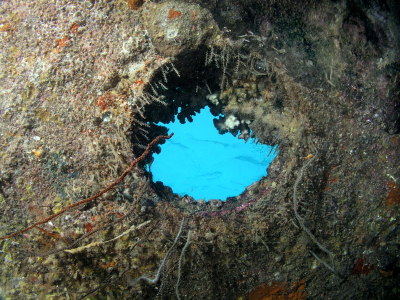

“As we rose in slow motion up the ghostly wall of the port bow, our running lights reflected off the still-unbroken glass of portholes in a way that made me think of cats’ eyes gleaming in the dark. In places, the rust about them formed eyelashes, sometimes tears. As though the Titanic were weeping over her fate. Near the upper railing- still largely intact- reddish –brown stalactites of rust hung down as much as several feet, looking like long needle-like icicles. This phenomenon, the result of iron-eating bacteria, was well known, but never had they been seen on such a massive scale. I subsequently dubbed them “rusticles”- a name which seems to have stuck” (2).

Now a joint effort from scientists in Spain and Canada has uncovered the DNA signature of one of a handful of bacterial agents that lie at the heart of the rusticle phenomenon. By removing stalactite pieces from the hull of the Titanic and performing a battery of elucidative phenotypic and chemotaxonomic tests, Christina Sanchez-Porro and others have homed in on the true identity of one salt-loving microbial wreck heister called Halomonas titanicae (3).

H.titanicae, dubbed BH1, is part of a larger family of bacteria that until now had never been observed so deep below the ocean surface. It uses iron as an inorganic source of energy, oxidizing it and leaving rust behind as a waste product. For many of the 27 bacterial strains now known to live in the rusticles, the deep sea conditions are not sufficiently acidic for growth (2). They get around this by manufacturing a more favorable dwelling of “highly viscous slime” that encapsulates them away from seawater and gives them an acidic habitat in which to flourish (2). But bacteria are not the only organisms feasting on the spoils of this particular maritime tragedy. Wood-borers have all but decimated much of the exquisite woodwork in the ship’s interior although the high density teak wood found in many of the railings, staircases and roof trims has proven to be remarkably unyielding to these voracious assailants (2).

Opinions differ over whether the havoc that bacteria such as BH1 are wreaking should be left to continue unabated (1) Ontario Science Center biologist Bhavleen Kaur believes that the bacterial goings-on aboard the Titanic could be used to help us better understand and halt the breakdown of other manmade sea structures such as offshore oil rigs and gas pipelines (1,4,5). Microbial ‘iron munching’ might even find application in recycling and disposal workflows (5). Some heritage devotees are less than happy about such proposals preferring instead to promote efforts to halt H.titanicae in its tracks and preserve the wreck for posterity.

While perhaps desirable, going head-to-head with nature’s forces seems impracticable given the sheer speed at which the wreck is succumbing to bacterial breakdown. Canadian civil engineer Henrietta Mann posited that twenty years from now there may be little more than a “rust stain on the bottom of the Atlantic” marking the location where the Titanic’s shadowy grave once lay (4,5). It is a sobering thought that such a fate should befall what was once a 50,000 ton steel leviathan of a ship (5). Extensive video footage and photographs may soon become the only means we have by which to remember the Titanic’s “very human story” (4,5).

Further Reading

- Rachel Kaufman (2010) New Bacteria Found On Titanic; Eats Metal, National Geographic News, December 10th, 2010, See http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/12/101210-new-species-bacteria-metal-titanic-wreck-science/

- Robert Ballard (1984) The Discovery Of The Titanic: Exploring The Greatest Of All Lost Ships, Madison Press Books, Toronto, ON, p.116, p.208

- Sánchez-Porro C, Kaur B, Mann H, & Ventosa A (2010). Halomonas titanicae sp. nov., a halophilic bacterium isolated from the RMS Titanic. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology, 60 (Pt 12), 2768-74 PMID: 20061494

- Graham Smith (2011) First it was an iceberg, now it’s bacteria: Rust-eating species ‘will destroy wreck of Titanic within 20 years’, Daily Mail, 12th January, 2011, See http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1346446/Titanic-wreck-completely-destroyed-20-years-new-rust-eating-bacteria.html

- Rosella Lorenzi (2010) Titanic Being Eaten By Destructive Bacteria, Discovery News, 7th December, 2010, See