GPCRs

GPCRs

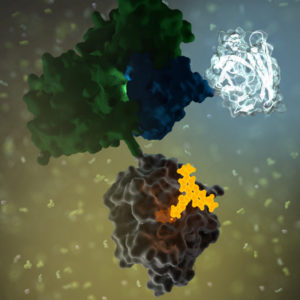

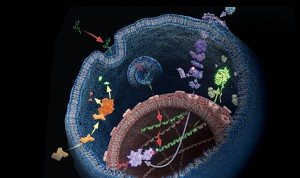

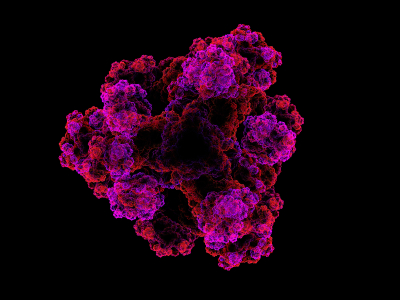

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a large family of receptors that traverse the cell membrane seven times. Functionally, GPCRs are extremely diverse, yet they contain highly conserved structural regions. GPCRs respond to a variety of signals, from small molecules to peptides and large proteins. Many GPCRs are involved in disease pathways and, not surprisingly, they present attractive targets for both small-molecule and biologic drugs.

In response to a signal, GPCRs undergo a conformational change, triggering an interaction with a G protein—a specialized protein that binds GDP in its inactive state or GTP when activated. Typically, the GPCR exchanges the G protein-bound GDP molecule for a GTP molecule, causing the activated G protein to dissociate into two subunits that remain anchored to the cell membrane. These subunits relay the signal to various other proteins that interact with or produce second-messenger molecules. Activation of a single G protein can result, ultimately, in the generation of thousands of second messengers.

Given the complexity of GPCR signaling pathways and their importance to human health, a considerable amount of research has been devoted to GPCR interactions, both with specific ligands and G proteins.

Continue reading “CRISPR/Cas9, NanoBRET and GPCRs: A Bright Future for Drug Discovery”

![Fig 4. Four point MMOA screen for tideglusib and GW8510. Time dependent inhibition was evaluated by preincubation of TbGSK3β with 60 nM tideglusib and 6 nM GW-8510 with 10μM and 100μM ATP. (A). Tideglusib [60 nM] in 10μM ATP. (B). GW8510 [60 nM] in 10μM ATP. (C.) Tideglusib [60 nM] at 100μM ATP. (D.) GW8510 [60 nM] at 100μM ATP. All reactions preincubated or not preincubated with TbGSK3β for 30 min at room temperature. Experiments run with 10μM GSM peptide, 10μM ATP, and buffer. Minute preincubation (30 min) was preincubated with inhibitor, TbGSK3β, GSM peptide, and buffer. ATP was mixed to initiate reaction. No preincubation contained inhibitor, GSM peptide, ATP, and buffer. The reaction was initiated with TbGSK3β. Reactions were run at room temperature for 5 min and stopped at 80°C. ADP formed was measured by ADP-Glo kit. Values are mean +/- standard error. N = 3 for each experiment and experiments were run in duplicates. Control reactions contained DMSO and background was determined using a zero time incubation and subtracted from all reactions. Black = 30 min preincubation Grey = No preincubation.](https://www.promegaconnections.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/journal.pntd_.0004506.g004-243x300.png)

Bacterial exotoxins are scary things. The names of the big three: Tetanus, Anthrax and Botulinum, are sufficient to evoke fear and conjure up images of agony, paralysis, mass hysteria, and permanently frozen Hollywood faces. The worst toxin stories are hard to forget. I can still remember the gruesome textbook case studies that accompanied my bacteriology college lectures. There were the home-canning-gone-horribly-awry botulism stories, the historical examples of agonizing tetanus poisonings, and the less lethal but still nasty cases of fast-acting staph toxins delivered to unsuspecting airline passengers in re-heated meals (avoid the ham sandwiches!). It’s all coming flooding back to me.

Bacterial exotoxins are scary things. The names of the big three: Tetanus, Anthrax and Botulinum, are sufficient to evoke fear and conjure up images of agony, paralysis, mass hysteria, and permanently frozen Hollywood faces. The worst toxin stories are hard to forget. I can still remember the gruesome textbook case studies that accompanied my bacteriology college lectures. There were the home-canning-gone-horribly-awry botulism stories, the historical examples of agonizing tetanus poisonings, and the less lethal but still nasty cases of fast-acting staph toxins delivered to unsuspecting airline passengers in re-heated meals (avoid the ham sandwiches!). It’s all coming flooding back to me. The ability to manipulate genes and proteins and observe the effects of specific changes is a foundational aspect of molecular biology. From the first site-directed mutagenesis systems to the development of knockout mice and RNA interference, technologies for making targeted changes to specific proteins to eliminate their expression or alter their function have made tremendous contributions to scientific discovery.

The ability to manipulate genes and proteins and observe the effects of specific changes is a foundational aspect of molecular biology. From the first site-directed mutagenesis systems to the development of knockout mice and RNA interference, technologies for making targeted changes to specific proteins to eliminate their expression or alter their function have made tremendous contributions to scientific discovery.