Approximately 30 million years ago, a retrovirus integrated into the germline of a common ancestor of baboons, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans. That endogenous retrovirus, now known as gammaretrovirus human endogenous retrovirus 1 (HERV-1), may provide clues about the aberrant regulation of gene transcription that enables tumor cells to grow and survive.

Understanding the Mechanism Behind Cancer Gene Expression

Scientists have long described the striking differences in gene expression, signaling activity and metabolism between cancer cells and normal cells, but the underlying mechanisms that cause these differences are not fully understood. In a recent Science Advances article, published by Ivancevic et al., researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder; the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and the University of Colorado School of Medicine report their efforts to identify endogenous retrovirus elements that might be part of the answer to the complex question of what biological events are responsible for the changes in gene expression in cancer cells.

The researchers hypothesized that transposable elements (TEs), specifically those associated with endogenous retroviruses could be involved in cancer-specific gene regulation. Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are the remnants of ancient retroviral infections that have integrated into the germline of the host.

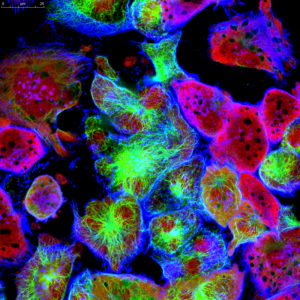

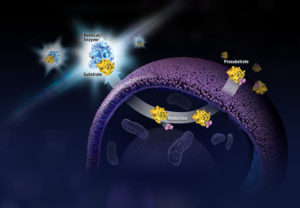

What if you could uncover a small but significant cellular response as your population of cells move toward apoptosis or necrosis? What if you could view the full picture of cellular changes rather than a single snapshot at one point? You can! There are real-time assays that can look at the kinetics of changes in cell viability, apoptosis, necrosis and cytotoxicity—all in a plate-based format. Seeking more information? Multiplex a real-time assay with endpoint analysis. From molecular profiling to complementary assays (e.g., an endpoint cell viability assay paired with a real-time apoptosis assay), you can discover more information hidden in the same cells during the same experiment.

What if you could uncover a small but significant cellular response as your population of cells move toward apoptosis or necrosis? What if you could view the full picture of cellular changes rather than a single snapshot at one point? You can! There are real-time assays that can look at the kinetics of changes in cell viability, apoptosis, necrosis and cytotoxicity—all in a plate-based format. Seeking more information? Multiplex a real-time assay with endpoint analysis. From molecular profiling to complementary assays (e.g., an endpoint cell viability assay paired with a real-time apoptosis assay), you can discover more information hidden in the same cells during the same experiment.