What animal can be found around the globe that outnumbers humans three to one? Gallus gallus domesticus, the humble chicken. The human appetite for eggs and lean meat drive demand for this feathered bird, resulting in a poultry population of over 20 billion.

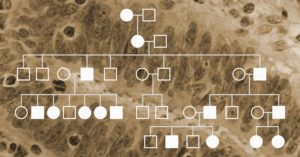

Controversy over the origin of the domestic chicken (when, where and which species) have lead some researchers to look for that information in the genomes of contemporary chicken breeds and wild jungle fowl, the candidates from which chickens were derived. By sequencing over 600 genomes from Asian domestic poultry as well as 160 genomes from all four wild jungle fowl species and the five red jungle fowl subspecies, Wang et al. wanted to understand and identify the relationships and relatedness among these species and derive where domesticated chickens first arose.

Continue reading “Identifying the Ancestor of a Domesticated Animal Using Whole-Genome Sequencing”