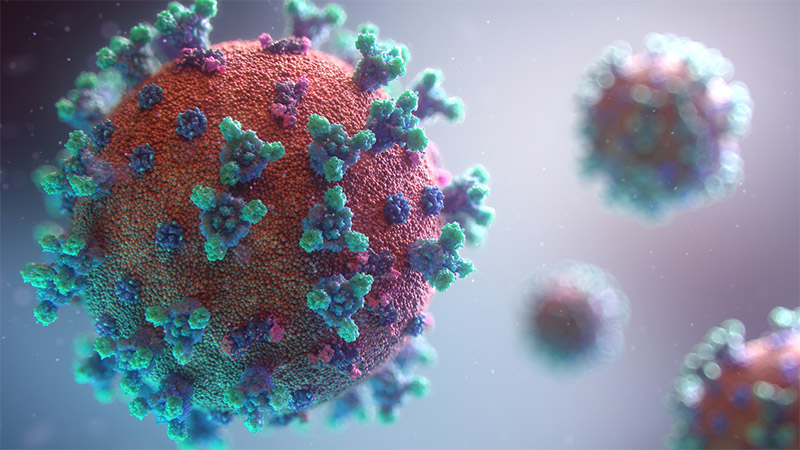

In the Northern hemisphere, the cold and flu season is about to start. Most years that means people schedule flu shots, dust off chicken soup recipes and stock up on tissues. If they start to feel sick, they stay home for a day or two, drink hot tea, eat warm soup and—for the most part— go on with their lives.

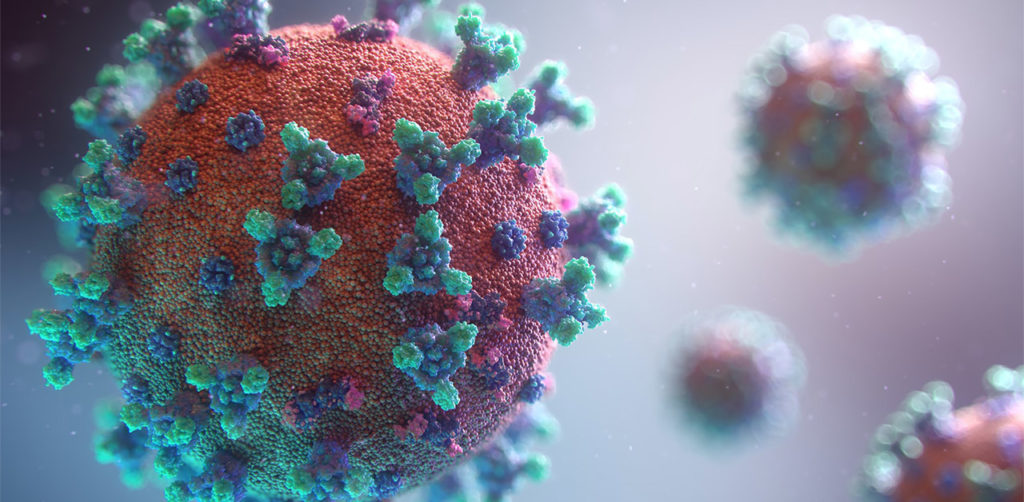

This is not, however, most years. This year the world is battling a pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2. Symptoms of COVID-19, the disease caused by this virus, mirror those of the flu and common cold, and that overlap in symptoms is going to make life more complicated. Most years, a mild cough or minor body aches wouldn’t even warrant a call to the doctor. This year these, and other undiagnosed cold- and flu-like symptoms, won’t be easily ignored. They could mean kids have to stay home from school, and adults have to self-quarantine from work, for up to 2 weeks. In years past people might have been comfortable treating their symptoms at home, this year people will want answers: Is it the flu? Or is it COVID-19?

Continue reading “Increasing Testing Efficiency with Multiplexed Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A and B”