Today’s post is written by Michael Curtin, Senior Product Manager, Reporters and Signaling.

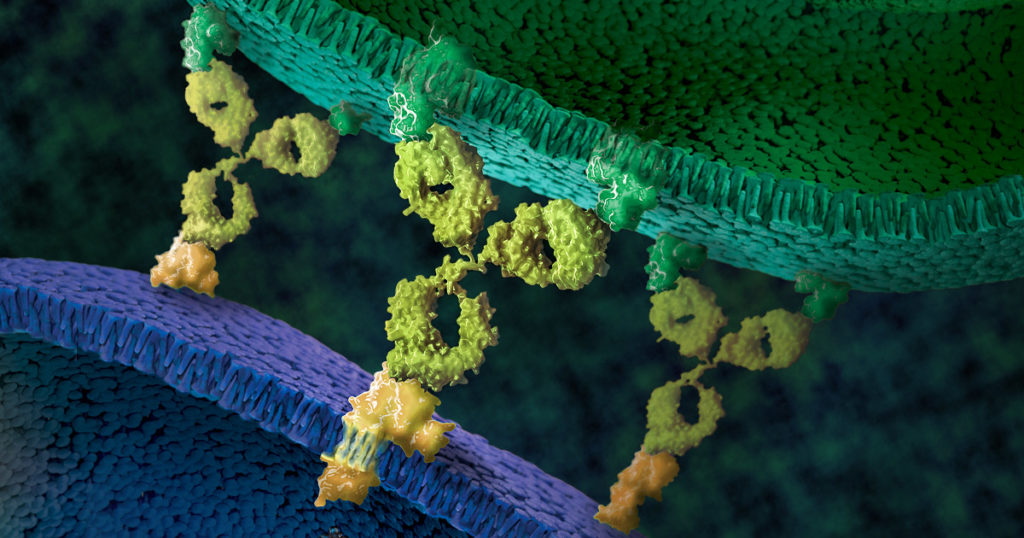

Inflammation is a defense mechanism that the body employs in which the immune system recognizes and removes harmful and foreign stimuli and begins the healing process. Inflammation can be either acute or chronic. Chronic inflammation is also referred to as slow, long-term inflammation and can last for prolonged periods (several months to years); chronic inflammation is caused by immune dysregulation. This typically takes the form of the body’s inability to resolve inflammation resulting from overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from dying cells (2). Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) is the primary cytokine involved in many common inflammatory diseases and is where many therapies targeting inflammation are focused.

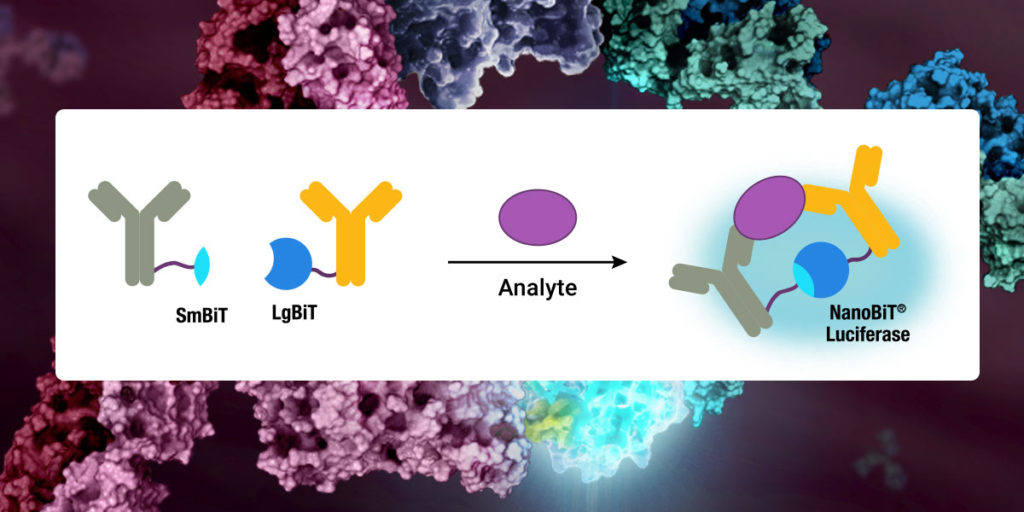

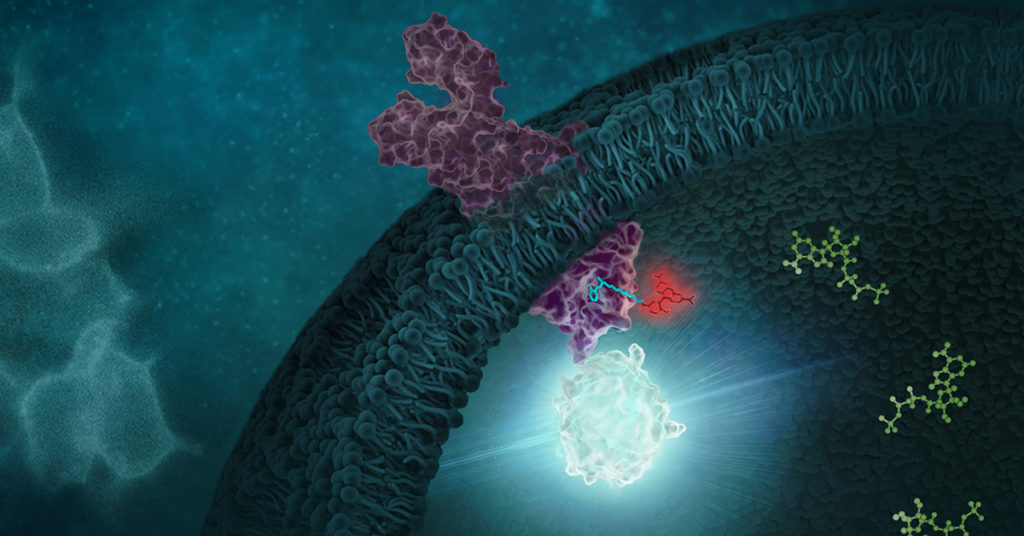

Recent research that RIP kinases (RIPK1 and RIPK3) are important regulators of innate immunity via their key roles in cell death signaling during cellular stress and following exposure to inflammatory and infectious stimuli. RIPK1 has an important scaffolding role in pro-inflammatory signaling where it interacts with TRADD, TRAF1 TRAF2, and TRAF3 and TRADD can act as an adaptor protein to recruit RIPK1 to the TNFR1 complex in a TNF-dependent process. RIPK1 plays a kinase activity-dependent role in both apoptotic and necroptotic cell death. A review article by Speir et al. (1) discusses the role of RIP kinases in chronic inflammation and the potential of RIPK1 inhibitors as a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of chronic inflammation. RIPK1 or Receptor Interacting Protein Kinase 1 is a serine/threonine kinase that was originally identified as interacting with the cytoplasmic domain of FAS. Promega offers several reagents that make studying RIPK1 easier- these include our RIPK1 Kinase Enzyme Systems which includes RIPK1 (Human, recombinant; amino acids 1-327), myelin basic protein (MBP) substrate, reaction buffer, MnCl2, and DTT and is optimized for use with our ADP-Glo Kinase Assay.

Continue reading “RIPK1: Promising Drug Target of Chronic Inflammatory Diseases”