The truth is that much of what we were told in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic was not entirely accurate. Many of the messages in the United States and other countries implied that the disease was “mild” for anyone who was not elderly or did not have a pre-existing respiratory condition. We were told the main symptoms were fever, coughing and difficulty breathing. It would be like a bad cold.

None of that is false. Data still shows that elderly individuals and those with pre-existing conditions are the most likely to experience severe disease. However, over the past few months we have seen how the SARS-CoV-2 virus can present serious complications in almost every organ system, and how its effects aren’t limited to the most vulnerable populations. We have also seen a growing number of cases where individuals are still experiencing life-altering symptoms for months after their supposed recovery.

To gain a full understanding of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, we have to explore every system in the body and track down the causes of all the unexpected clinical presentations of the disease.

How does COVID-19 affect other body systems?

COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory disease. The most common symptoms are fever, coughing and difficulty breathing. Some people have described it as a bad cold, while many have required hospitalization or ventilators. CDC lists several non-respiratory symptoms such fatigue, muscle/body aches, sore throat, congestion, and several digestive issues. The loss of taste and smell has also been a widely discussed symptom.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus gains access to cells by binding to the ACE2 receptor. This receptor normally binds an enzyme responsible for lowering blood pressure. It’s highly expressed in many parts of the respiratory system, but also in many other tissues throughout the body. This widespread distribution of ACE2 is one of the reasons why COVID-19 can cause so many different symptoms. If the virus manages to bind ACE2 in other tissues—the β cells of the pancreas, for example—it can disrupt a wide variety of bodily functions.

The other major factor in severe COVID-19 is the irregular immune response provoked by SARS-CoV-2. The infection is closely associated with a decrease in circulating immune cells such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as an increase in inflammatory markers. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are released by the innate immune system in response to an infection. In some cases of COVID-19, cytokine production spirals out of control into a condition called a “cytokine storm.” This triggers extreme inflammation, causing immune cells to damage our own cells. In many cases, the cytokine storm causes more harm than the original infection. Cytokine storm is one of the key triggers of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in COVID-19 patients, and it is suspected to cause many of the other life-threatening symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Are these symptoms actually more common with COVID-19 than other viruses or emerging infectious diseases such as SARS or MERS? It’s hard to tell. Many of the non-respiratory symptoms also occur with these other diseases, but the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic make it difficult to compare frequency. For example, there have only been around 8,400 cases of SARS worldwide since 2003. According to Johns Hopkins, there have been over 59 million cases of COVID-19 (as of November 24, 2020). A single doctor may see dozens of complex COVID-19 cases with multiple systems affected, while the case numbers of SARS are low enough that reports of unique symptoms are scarce.

Overall, the complexity of COVID-19 is a reminder that this is a novel disease caused by a previously unknown virus. Our understanding of the infection has progressed at an amazing rate since it was first reported, but we still have so much more to learn.

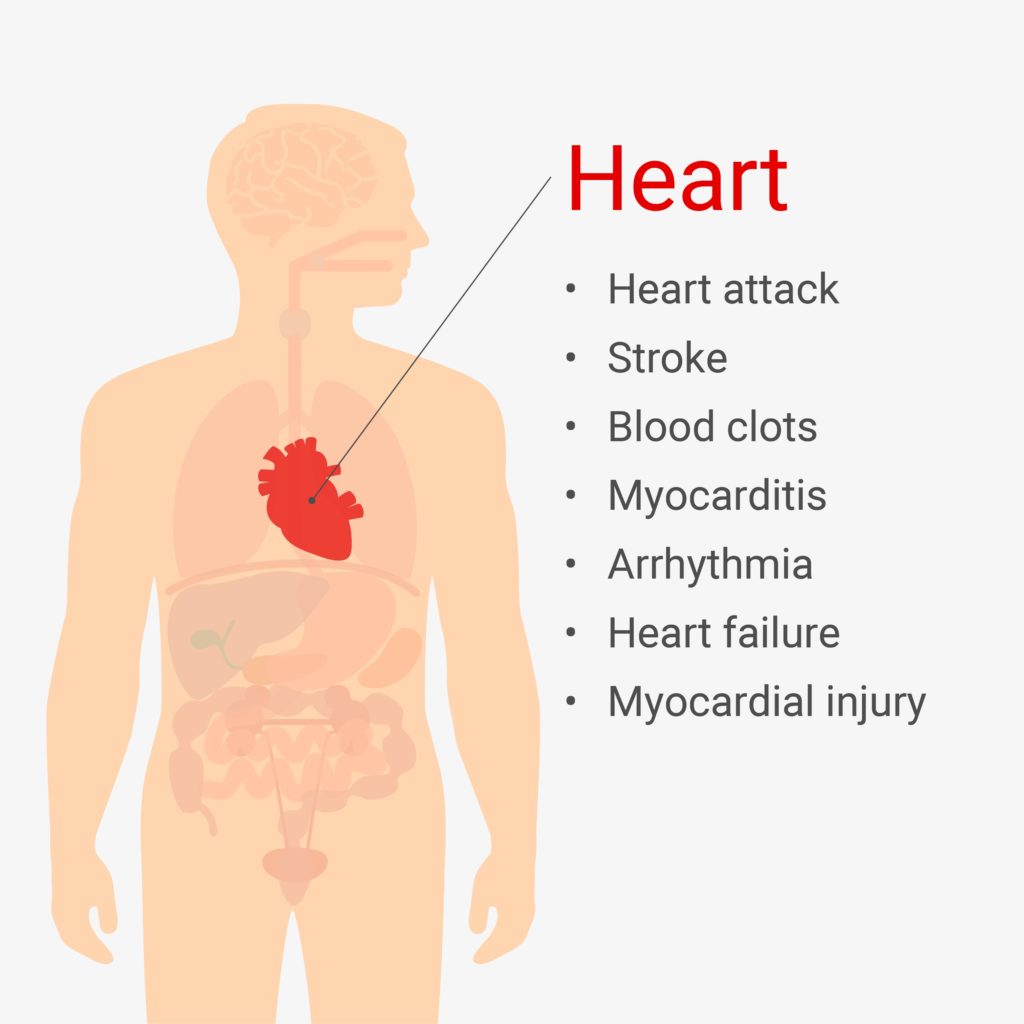

Cardiovascular System

Outside of the lungs, the cardiovascular system is possibly the most impacted by COVID-19. Inflammation and cytokine storm are the most likely cause of many of these clinical presentations, but data on ACE2 expression in cardiac cells suggests that direct viral attack is also a factor.

Patients with “severe” COVID-19 have significant rates of major cardiac events such as cardiac arrest. An early study from Wuhan, China, the first epicenter of the pandemic, found that 22% of ICU patients showed signs of acute damage to the heart muscle, while another recent study estimated as high as 36%. A different Wuhan study found that 23% of hospitalized patients experienced heart failure. There are also reports of new-onset atrial fibrillation, an irregular heart rate that occurs when the upper and lower chambers of the heart beat out of sync.

Myocarditis, a common feature of viral infections, has also been reported with many COVID-19 cases. This inflammation of the heart muscle often results in chest pains, shortness of breath, and arrhythmia. If blood clots begin to form, it can also lead to a heart attack or stroke.

Blood clot formation is also a risk with COVID-19, as the virus has been shown to influence several factors involved in coagulation. By disrupting the normal coagulation cascade, the virus induces a high risk of blood clots, including venous thromboembolism and ischemic stroke. This is likely related to hypoxia caused by a decrease in respiratory function, as well as general inflammation, but platelet hyperactivity as a result of ACE2 binding has also been implicated.

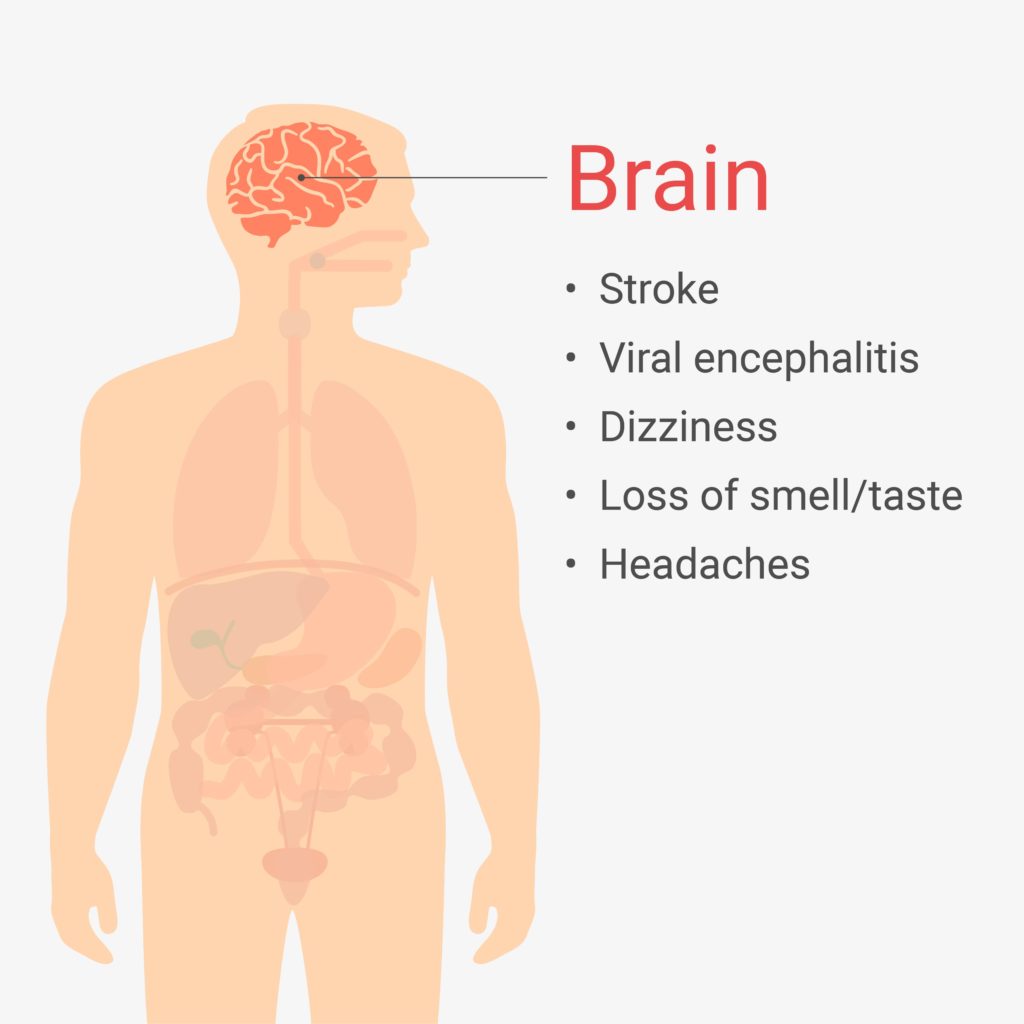

Nervous System

Headaches and dizziness have been documented in COVID-19 patients of every level of disease severity, with some frequency estimates as high as 42%.

Some of the more serious symptoms, however, involve SARS-CoV-2 entering nervous tissue. ACE2 is found on neurons, and direct entry of the virus into structures such as the brain stem can cause the loss of autonomic control over breathing. Other symptoms are similar to meningoencephalitis, an inflammation of the brain that can lead to altered mental states. One case study describes a patient who developed delusions and the inability to walk, among other serious neurological symptoms. This patient tested negative for COVID-19 via nasopharyngeal swabs, but antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 were found in his cerebrospinal fluid.

As mentioned earlier, there are many reports of COVID-19 leading to ischemic stroke, especially among older patients and those with cardiovascular risk factors. Cerebral hemorrhage can also occur if the virus binding to ACE2 causes a breakdown of the blood brain barrier.

One interesting symptom that seems to be widespread is the loss of taste and smell. Patients describe the complete inability taste or smell anything, sometimes continuing for several days or weeks after recovery. ACE2 is expressed in cells of the olfactory bulb, and invasion of those cells by SARS-CoV-2 could lead to a disruption of those senses.

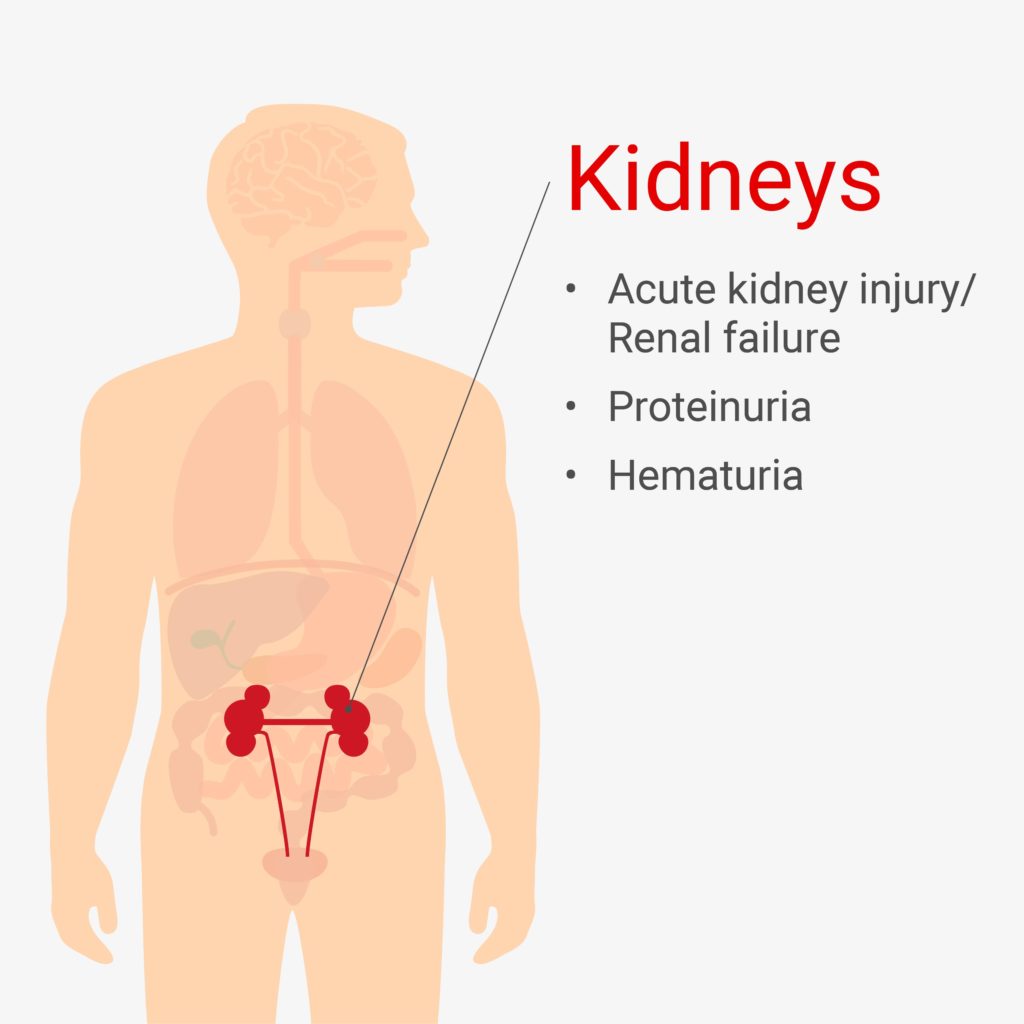

Kidneys

Acute kidney injury (AKI, or acute renal failure) is one of the most fatal complications of COVID-19, and it occurs in a high proportion of hospitalized patients. One study in New York City hospitals found that 37% of patients were diagnosed with AKI, and 14% required dialysis. In a different study, up to 87% of critically ill patients showed blood or protein in their urine, which can also indicate damage to the kidneys. Histopathological studies have shown damage to kidney tubules that suggests direct infection of renal cells by SARS-CoV-2.

Liver and Pancreas

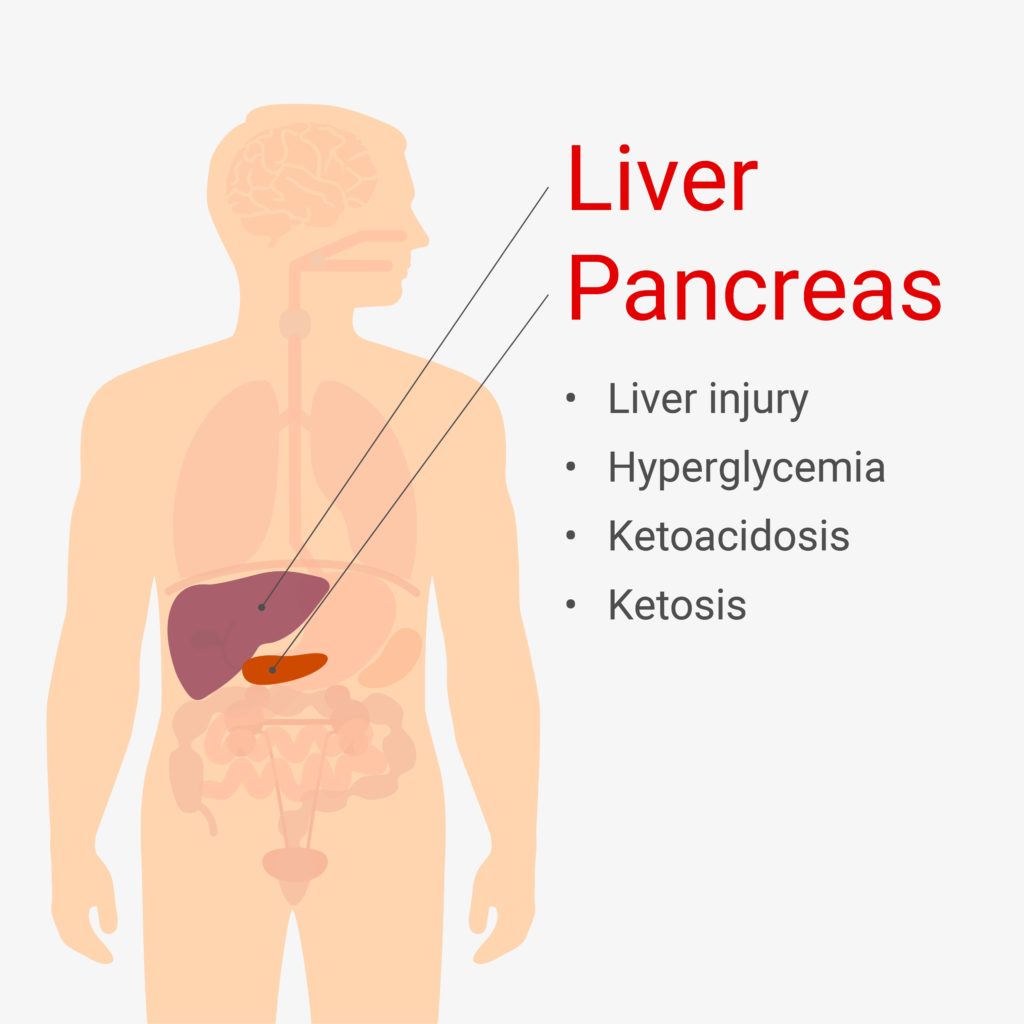

Diabetes has long been understood as a risk factor for developing severe COVID-19, but even non-diabetic COVID-19 patients have shown abnormal glucose metabolism. These symptoms include hyperglycemia, ketosis and ketoacidosis. Inflammation from cytokines may affect the β-cells in the pancreas, which are responsible for producing insulin. β-cells also express ACE2, so it is possible that the virus is directly attacking these cells, resulting in a decrease in insulin production. This has not yet been demonstrated in published literature, but previous research on SARS-CoV showed evidence of ACE2 binding in the pancreas.

Liver failure is the fourth most fatal complication of COVID-19, after ARDS, heart failure and renal failure. Liver injury is most common in COVID-19 cases that are otherwise considered severe, but it can be a major complication on its own. Hyperinflammation and metabolic damage are likely causes of liver damage, but ACE2 expression on the cells lining the bile duct in the liver suggests that direct binding may be a factor.

Digestive System

Many people diagnosed with COVID-19 report diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain during their illness. These can occur at any level of disease severity, and while they’re unlikely to be life-threatening on their own, they represent another potential mode of transmission. Live SARS-CoV-2 viral particles have been detected in human feces, even after symptoms have gone away. While there are currently no reports of transmission via feces, this brings up an important piece of the pandemic response. Wastewater monitoring can help predict where outbreaks are about to occur by detecting a rise in the level of viral particles or RNA present in sewage.

Long-Term COVID-19

There is little research at this point about the long-term effects of COVID-19, but there are thousands of patients who continue to struggle with mild to life-changing symptoms long after their “recovery.” These symptoms include pain, numbness, and chronic fatigue. Ed Yong writes in The Atlantic about patients who wake up in the night gasping for breath or experience debilitating headaches. Some of these symptoms overlap with conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome and dysautonomia, which is a disturbance of the autonomic nervous system. Many of these patients are still unable to return to “normal life” six or more months later.

The sheer numbers of these “long-haulers” contradicts the idea that COVID-19 is a “mild” infection that lasts 14 days. While extensive resources have been funneled into understanding the virus and developing drugs and vaccines, chronic COVID-19 is an area that will require much of its own research. In the meantime, changing the narrative around the severity of COVID-19 could influence how seriously people take precautions. As public health professor Nisreen Alwan tells Ed Yong, the definition of recovery must be expanded beyond life and death. “Death is not the only thing that counts. We must also count lives changed.”

There is no dichotomy between death and a “mild” infection. Many of the non-respiratory symptoms can be life-changing, even without the unique symptoms experienced by long-haulers. COVID-19 symptoms are complex and surprising, and we must continue to work towards solutions while protecting ourselves and everyone around us.

Resources

- Gupta A, et al. 2020. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 26(7)

- AlSamman M, et al. 2020. Non-respiratory presentations of COVID-19, a clinical review. Am J Emerg Med. S0735-6757(20)30847-0.

Latest posts by Jordan Villanueva (see all)

- Tackling Undrugged Proteins with the Promega Academic Access Program - March 4, 2025

- Academic Access to Cutting-Edge Tools Fuels Macular Degeneration Discovery - December 3, 2024

- Novel Promega Enzyme Tackles Biggest Challenge in DNA Forensics - November 7, 2024