It seemed like the rain was never going to stop. It started in the morning, and when I left work around 5pm, it was still coming down hard. I took my normal route home through a back country road. As I turned right onto Fitchrona Road, a long line of cars came into view. There’s usually some congestion leading to the stop sign ahead. Except today, something was different. About 20 yards of the road ahead was submerged in water.

Most of the cars charged through. The water seemed to be only 3-4 inches deep. I was confident my SUV could make it. Luckily, it did. When I got home, I received a text from my husband. He said, “It’s flooding everywhere, I tried three different roads, and they were all under water. I’m parked with a bunch of other cars at the gas station. We’re going to wait here until the water goes down.” He also sent a photo of a wide, turbulent river. An eerie green light reflected off the river surface—it was a traffic light standing tall in the middle of the water. Also in the river were two cars, wheels half submerged. It took me a few moments to realize that the “river” was flowing on the major intersection of Highway 151 and McKee Road. My city was under water.

On August 20, 2018, southern Wisconsin experienced one of the most disastrous floods in the past century. Madison, the city I call home, and surrounding areas received bursts of extreme rainfall, some exceeding 14 inches within 24 hours. How bad was it? The previous 24-hour rainfall record in Wisconsin was 11.7 inches. That was in 1946.

My husband made it home safely, after waiting for half an hour at the gas station for the water to recede. We later found that water had seeped into our basement, wetting the carpet. The smell of dirty wet socks lasted for more than two weeks. But I’m not complaining. A friend of mine had water gushing through her basement windows like a waterfall. Hundreds of cars were stalled in high water around the city. More than 80 people were forced to stay overnight at a Costco in Middleton when the area around the warehouse was flooded with over a foot of water. East Johnson Street, a major road along the isthmus between two of Madison’s largest lakes was under water for weeks. One man tried to escape from his flooded car, but was sucked under water. His body was found in a retention pond about a third of a mile away.

Emergency officials estimated the damage caused by the storm and flooding totaled around $209 million dollars. As bad as this seems, the worst is yet to come. In a report by Dr. Daniel Wright, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he states “The August 20 storm was not unprecedented, and similar or larger storms can be expected in the coming years. This problem is likely to be exacerbated by continued climate change impacts on extreme rainfall. The fact that we haven’t seen flooding like this in the past in Madison is probably partly the result of luck.”

The idea that extreme rainfall is becoming more common is nothing new. In a presentation back in 2009, Dr. Steve Vavrus, Senior Scientist at the Nelson Institute Center for Climatic Research, stated “If it seems like heavy rainfalls around here have become more common lately, it’s because it has.” Warming temperatures associated with climate change are likely to blame. The best accepted explanation among scientists for how warming temperatures can increase heavy rainfall is fairly simple. Warmer surfaces, land or ocean, tend to evaporate more, which generates more moisture in the air. Just like when you crank up the fire under a kettle of boiling water, more water will evaporate. When conditions are right for heavy rainfall, such as a big thunderstorm or a slow-moving front, “The atmosphere can better wring out the greater availability of moisture and produce a heavier rainfall event,” says Dr. Vavrus. This means that in the past where certain storm conditions may generate 1 inch of rain, future conditions may generate 2 or more inches. This trend is well underway—the amount of rainfall in the heaviest storms in the Midwest has already increased by 37% from 1958 to 2012. Climate models predict that by 2055, the frequency of heavy precipitation events (>2 inches of rainfall) in Wisconsin will occur once every 8 months, 25% more frequent than in 1980.

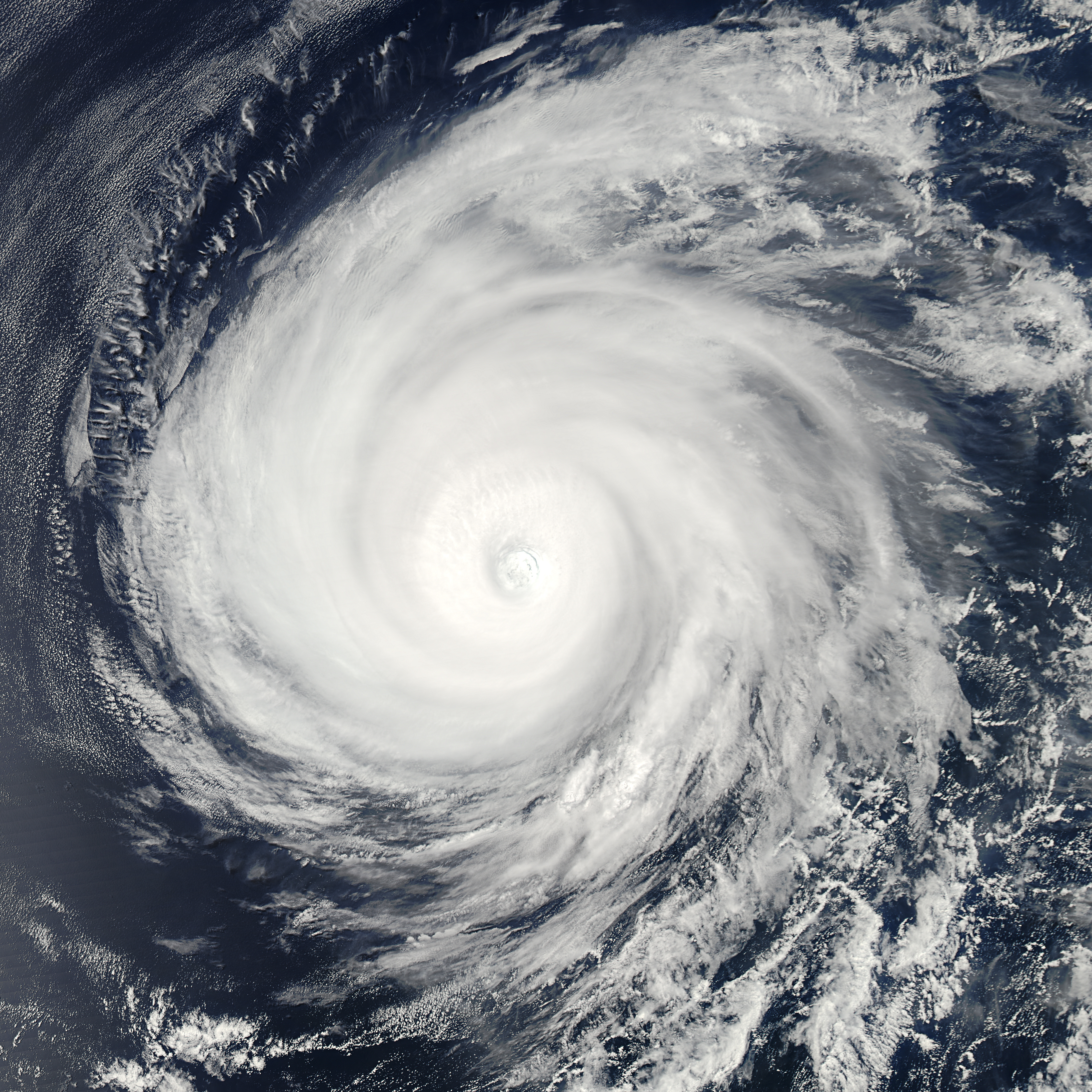

What’s happening around Madison is just a snapshot of what’s going on around the world. Intense hurricanes have also become more common globally partly due to warmer sea temperatures. The National Climate Assessment states that “the intensity, frequency, and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes, as well as the frequency of the strongest (Category 4 and 5) hurricanes, have all increased since the early 1980s.” Just last week, Hurricane Florence dumped 30–36 inches of rain across North and South Carolina, causing massive flooding throughout the two states. More than 340,000 people experienced power outage. 33 people lost their lives. The damage caused by Hurricane Florence puts the flood here in Madison to shame.

For most of us, climate change seems distant. It’s hard to imagine how an increase of a few degrees can affect our daily lives. We see storms, hurricanes, and flooding in the news all the time, yet they don’t seem like an immediate threat. But when they happen in your backyard (or basement!), the effect of climate change becomes a lot harder to ignore. Unfortunately, as temperatures continue to rise, more people will experience severe weather first-hand.

A week after the August 20 storm, my family went hiking along Picnic Point, a mile-long peninsula along the south shore of Lake Mendota, Madison’s largest lake. At the midpoint of the hiking trail, there’s a small shaded beach. My kids love to wade into the water and play in the sand there. That day, however, there was no beach—water now went up to the rocks. Several lakes around Madison have reached the 100-year flood level, the estimated water level that would occur only once every 100 years. “Will the beach come back?” asked my 6-year old son. “I don’t know,” I said, “but I sure hope so.”

Latest posts by Johanna Lee (see all)

- Microfluidic Organoids Could Revolutionize Breast Cancer Treatment - March 25, 2025

- Bacteria From Insect Guts Could Help Degrade Plastic - January 28, 2025

- A Diabetes Drug, Metformin, Slows Aging in Male Monkeys - December 19, 2024