Mpox (formerly known as Monkeypox; 1) has been making the news lately. The declaration by the WHO Director-General naming mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC; 2) has a lot of people wondering what it is, how it spreads and how concerned they should be. Understandably, we are all a little jumpy when we start hearing about a new viral disease, but the virus that causes mpox (monkeypox virus) isn’t new.

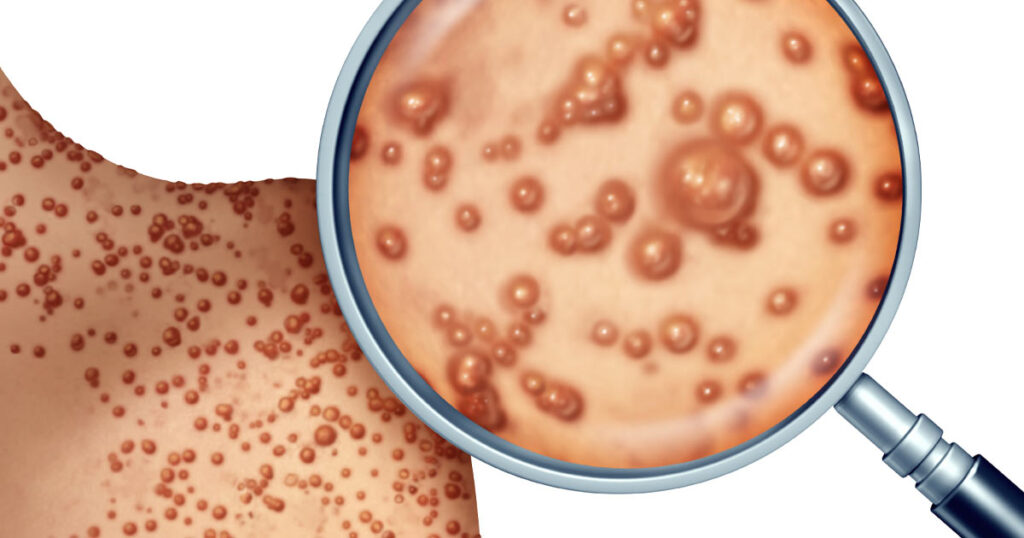

A member of the Poxviridae family, the monkeypox virus is closely related to the variola virus that causes smallpox; however, monkeypox causes milder symptoms and is less fatal (1). While the virus gained its unfortunate name from its discovery in monkeys in 1958 (3), the original source of the disease remains unknown. The virus exists in a wide range of mammals including rodents, anteaters, hedgehogs, prairie dogs, squirrels and shrews (4) and can spread to humans through close contact with an infected individual or animal. Symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle and back pain, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion (3). The most distinguishing symptom is the blister-like rash.

Much like its cousin smallpox, mpox spreads in humans through close contact with the infectious rash, scabs, or bodily fluids, as well as through contact with contaminated clothing or linens. The virus can also spread through respiratory secretions with prolonged face-to-face contact or during intimate physical contact. Because it is a zoonotic virus, it can also be transmitted through contact with an infected animal either through a scratch or bite, or by preparing or eating meat and other products from an infected animal.

Making the Move to Humans

In 1970, a 9-month-old baby in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, DRC) became the first reported case of mpox (called monkeypox at the time) in humans (6). Since that time, mpox has become endemic in West and Central Africa, with the number of cases growing over time (6). Along with the increase in case numbers, the age of those infected has also been rising. In the 1970s, the virus mostly infected young children (median age 4 years); in the years between 2010 and 2019, that age rose to 21.

Ironically, some of the increase in mpox cases might be because we successfully eradicated smallpox. The two viruses are similar enough that the smallpox vaccine offered approximately 85% cross-protection against mpox (5). Routine vaccination against smallpox ceased after the 1980s, when the world was declared free from the virus. As a result, there is now a much larger population who might be more vulnerable to a mpox infection because they don’t have the partial protection from the smallpox vaccine. There are vaccines that we can use against mpox. In the United States, the most current recommendations for mpox vaccination can be found on the CDC website (6).

It is important to note that although many—but not all—cases

have been reported in men who identify as men who have sex with men (MSM), mpox

is not a sexually transmitted disease. Anyone can get this virus, and any type

of close contact with an infected person can result in infection (3).

Emerging Global Relevance

Mpox has been a known pathogen for humans since 1970, so why have the recent outbreaks garnered such attention? Although the WHO considers the virus endemic in parts of Africa, cases outside these regions have been rare, and typically linked to recent travel to or through an endemic region. The recent outbreaks in 2022 were different. With these outbreaks, mpox appeared more or less simultaneously in many different countries and across different continents, which was something we had never seen before. In early June, 2022, the WHO reported 600 confirmed or suspected cases in 30 different countries (7), by July, 2022, that number grew to more than 14,000 cases in 70 countries (8). This multi-country outbreak led to declaration of an PHEIC in July of 2022 (2). The declaration was driven by concerns that the broad geographical dispersion and rapid spread meant that the virus was spreading undetected via human-to-human contact and had been for some time. The WHO declared the 2022 mpox PHEIC over in May of 2023 following a steady decline in global cases (2).

Monitoring and Testing for Monkeypox Virus

The current global mpox surge is a dynamic, rapidly changing public health concern. Although most patients can be treated in an outpatient setting, there are rare instances of more severe disease. Currently in the United States, a PCR test is needed to confirm a mpox infection (9).

Any time there is an outbreak of an infectious disease, public health officials want to try to contain the outbreak and stop the disease from spreading. With mpox, officials in some areas are looking to lessons from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic to find ways to better protect their communities. One approach is to monitor wastewater to try to detect the presence of the infectious agent early. Testing wastewater for infectious diseases such as SARS-CoV-2 and mpox can help public health departments get a better idea of the rate of infection in their areas and even identify communities where the disease is just emerging. This information can help officials decide where to focus public outreach activities as well as where to send valuable medicine and vaccines.

Read how researchers at UNLV are using wastewater surveillance to detect and monitor monkeypox virus and other infectious agents in the Las Vegas area.

Now Available: Kits for Wastewater Viral RNA/DNA Extraction.

Developing your own assay to detect monkeypox virus in wastewater? The GoTaq® GoTaq® Enviro Master Mix, 2X, provides a great starting point.

Promega Applications Scientists developed a protocol for purifying total nucleic acid (TNA) from wastewater for monkeypox detection. View the product application here.

Treatment and Vaccines

Although there are no treatments specifically for mpox, antiviral treatments that were effective against smallpox may be used with mpox because the two viruses are so genetically similar. For communities experiencing outbreaks in the United States, a vaccine is available. Ideally, people at risk of mpox exposure should be vaccinated before exposure; however, people can also be vaccinated after exposure (post-exposure prophylaxis). When given within a few days of exposure, the vaccines can help prevent illness. When a longer time has lapsed between exposure and vaccination, the vaccine may still help reduce disease symptoms. More information is available on the CDC website (6).

Conclusions

The threat to public health from zoonotic pathogens is not new. West Nile virus, plague and Lyme disease are all examples of zoonotic diseases that have and continue to cause dangers to public health. Scientists estimate that three out of every four new or emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals (10). The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic clearly illustrated the chaos an emerging zoonotic disease can cause when it adapts to spread rapidly in humans. For this reason, scientists around the world spend their lives studying animal diseases, and institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) pay close attention to new outbreaks.

last updated 09/09/2024

References

- About Mpox, CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/about.html

- Accessed September 3, 2024.

- WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. WHO website. Accessed September 3, 2024.

- von Magnus, P. et al. (1958) Acta Path Microbial Scand. 46, 159.

- Mpox in Animals and Pets, CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/index.html Accessed September 3, 2024.

- Bunge, E.M. et al. (2022) PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010141.

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS Vaccine for Mpox Prevention in the United States, CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/vaccines/vaccine-considerations.html Accessed Septmber 3, 2024

- Kozlov, M. (2022) Nature 606, 15.

- World Health Organization Archive: 2022-23 acute outbreak phase https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/#7_Archive:_2022-23_acute_outbreak_phase Accessed September 3, 2024.

- Mpox Clinical Testing. CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/index.html Accessed September 3, 2024.

- Zonotic Diseases CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/about-zoonotic-diseases.html? September 3, 2024.