Lynch Syndrome is the autosomal dominant hereditary predisposition to develop colorectal cancer and certain other cancers. This simple, one sentence definition seems woefully inadequate considering the human toll this condition has inflicted on the families that have it in their genetic pedigree.

They Called it a Curse

To one family, perhaps the family when it comes to this condition, Lynch Syndrome has meant heartache and hope; grief and joy; death and life. Their story is told by Ami McKay in her book Daughter of Family G, and it is at once both a memoir of a Lynch Syndrome previvor (someone with a Lynch Syndrome genomic mutation who has not yet developed cancer) and a poignant and honest account of the family that helped science put name to a curse.

“The doctors called it cancer. I say it’s a curse. I wish I knew what we did to deserve it.”

Anna Haab from Daughter of Family G (1)

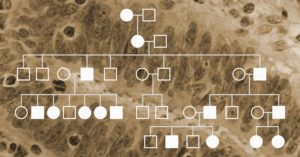

The scientific community first met “Family G” as the meticulously created family tree, filled with the stunted branches that mark early deaths by cancer. The pedigree was first published in 1913 in Archives of Internal Medicine (2). In the article, Dr. Alderd Warthin wrote: “A marked susceptibility to carcinoma exists in the case of certain family generations and family groups.” In 1925, an expanded pedigree of circles and squares was published in Dr. Warthin’s follow up study in the Journal of Cancer Research (3). But each circle and square in that pedigree denotes a person. Each line represents their dreams together for the future, and Ms. McKay wants us to know their names: Johannes and Anna, Kathrina, Elmer, Tillie, Sarah Anne (Sally); and—most importantly—Pauline. Because without Pauline there would be no story.

Pauline’s Story

It was Pauline’s, perhaps impulsive, decision to share her fears of an early death by cancer with an acquaintance, Dr. Warthin, that first brought her family’s ‘curse’ of cancer to the attention of the medical and scientific communities. Pauline Gross worked as a dressmaker in Ann Arbor Michigan in the late 1800s. More importantly though she was Ms. McKay’s great, great aunt, granddaughter of Johannes and Anna Haab, the daughter of Katherina Habb Gross and sister to Ms. McKay’s grandmother, Tillie Wheeler. It was through Pauline that Dr. Warthin learned her family’s history. She helped him compile their pedigree, introduced him to relatives and encouraged those she loved to seek out Dr. Warthin’s hospital for treatment. His hospital couldn’t save her though, when she was rushed there in 1919 for emergency surgery. The diagnosis: advanced cancer of the uterus.

Although he could not save Pauline, nor so many of her family members, Dr. Warthin was convinced that the predisposition to cancer found in her family was hereditary. It was revolutionary thinking for the time, when so many doctors and scientists were focusing on cures not causes. It was also, as Ms. Mckay ruthlessly highlights, thinking that was driven in part by Dr. Warthin’s personal beliefs in the principles behind the Eugenics movement. While Pauline’s vision for the future was one where men like Dr. Warthin helped her family escape the curse of cancer that haunted them, Dr. Warthin’s vision of the future was a world where her family, with its faulty pedigree, ceased to exist.

The Eugenics movement would have made life uncomfortable for a family with such close ties to cancer. Possibly that is why the Gross family scattered over the coming years. Michigan, Ms. McKay notes, was the first state to introduce a compulsive sterilization bill. Is it any wonder that family members moved away looking for a fresh start, tried to “forget their genes” as she describes it?

When Dr Warthin died in 1931, his successor, Dr. Carl Weller, continued his research on Family G, presenting further findings about the family at the 29th meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in 1936. Among the points he made was that members of Family G— who know their family’s history and seek medical help quickly with any onset of symptoms— were much more likely to survive. The example he highlighted was a woman, now a grandmother, who had survived cancer twice. Although he didn’t mention it, her name was Tillie Wheeler, and she was Pauline’s sister. The scientific community, however, was still uncertain about the idea of a hereditary nature of cancer. When Dr. Weller died suddenly in 1956, the research on Family G ground to a stop.

Dr. Lynch and New Beginnings

Interest in Family G was revived in the mid-1960s, when an oncologist, Dr. Henry Lynch, and his associate, Anne Krush, a social worker specializing in medical research, reached out to Dr. Weller’s successor. They had recently published a study of a family in Nebraska with a cancer history very similar to Family G. That study had been limited in size, whereas the information about Family G collected by Dr. Warthin and Dr. Weller was extensive, covering over 75 years. A review of the Family G data gave them a growing belief that they were on the path to answers. With new enthusiasm, the pair began to reach out to the members of Family G. Their thoughtful and forthright approach won over family members, two of whom declared Dr. Lynch an honorary member of Family G.

Dr. Lynch and Ms. Krush spent years tracking down family members and collecting more data. They also collected data on other families with similar history of cancer, especially colorectal cancer. By the early 1990s, they had amassed quite a collection of samples from families afflicted with an apparent inherited predisposition to colorectal cancer. When researchers discovered the link between mutations in a gene called MSH2 and colorectal cancer, the head of the lab, Dr. Vogelstein, reached out to Dr. Lynch to see if they could collaborate. Dr. Vogelstein wanted to investigate if the mutations in MSH2 or similar genes explained the affliction of the families that Dr. Lynch had been studying. Dr. Lynch called the condition hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), but it was soon to be renamed Lynch Syndrome, in part to accommodate the fact that it encompassed more than just colorectal cancer. This collaboration brought the hope that soon science would be able to point to a mutation in a gene (or genes) that was passed down through these families’ pedigrees, bringing cancer with it.

Knowledge is Power

If all that Ms. McKay’s book did was trace the history of this family with the world of science and medicine, it would be a book worth reading, but Daughter of Family G is more than a history of the author’s family. The book is also a tribute to her parents, especially her mother Sarah Anne (Sally), who faced life with hope and cancer with bravery. It was Sally who encouraged her daughter to stand strong and seek answers, and Sally who continued to hope that science would, in her lifetime, offer the answers that her great aunt Pauline had hoped for in 1898.

Sally had great faith that Dr. Lynch and the scientists he worked with would find the answer. She provided blood and tissue samples, filled out questionnaires, and she encouraged her children to help in the efforts as well. Finally, in 1999, the team of genetic researchers that Dr. Lynch had been working with found a way around the genetic roadblock that had kept the mutation for Family G hidden. The breakthrough came when a post-doc, Dr. Hai Yan, in a lab lead by Drs. Vogelstein and Kinzler was able to convert the human chromosome complement from diploid (two copies of each chromosome) to haploid. In essence, Dr. Yan had developed a way to split the two sets of chromosomes apart so that each set could be studied separately. This allowed them to identify deletions that were masked when both sets of chromosomes were studied together. Their solution was published in 2000 in Nature (4). For Dr. Vogelstein and his lab it meant success after years of frustration. For Sally and Family G it meant there was finally a way to know if they too would be afflicted with cancer.

Laying a Curse to Rest

Ms. McKay’s account of her family’s history puts some of our scientific past under an uncomfortably clear lens. She acknowledges the importance of Dr. Warthin first recognizing the hereditary nature of the cancer in her family but refuses to filter out the uncomfortable truths about the man himself. In the same way, she is brutally honest about the story of her own life. Beyond documenting the history of a family and science, beyond paying tribute to a mother who raised her children to seek truth and embrace knowledge, Daughter of Family G is the story of the author herself. It is a compelling narrative of growing up with the ever-present fear of cancer taking someone she loved, and her journey to confront that fear.

Ms. McKay describes her experience when her truth suddenly shifts from someone who could be affected to someone who knows she is. She highlights her fear and guilt when her oldest son also tests positive, and her pride in how he adapts to the news by choosing to live his life to the fullest every day. She reminds us of all the advances that science and medicine have made since those early days of wondering whether cancer could be hereditary. She reminds us of the power that comes with knowledge: knowing they are Lynch dispels the specter of the curse of cancer that haunted their ancestors.

It is, above all, a story of hope.

References

- McKay, Ami (2019) Daughter of Family. G. Alfred A. Knopf Canada, publisher.

- Warthin, A.S. (1913) Heredity with reference to carcinoma. Arch. Intern. Med. 12, 546–55.

- Warthin, A.S. (1925) The further study of a cancer family. J. Cancer Res. 9, 279–86.

- Yan, H. et al. (2000) Conversion of diploidy to haploidy. Nature, 403 723–4.

More Reading

Learn about another family affected by Lynch Syndrome, read Carrie Ketcham’s story in “Life with Lynch Syndrome”

Cancer genetics expert Heather Hampel wants every new colorectal tumor to be tested for Lynch Syndrome, read more in this article “Dreaming of Universal Tumor Screening“.

Learn more about Lynch Syndrome Testing and Detection at our website.