During graduate studies in Medical Microbiology and Immunology at the University of WI-Madison, a favorite class was an infectious disease course that included an exercise in designing the perfect pathogen. This was a thought experiment, a writing exercise. No laboratory experimentation was involved.

You might initially think of a perfect pathogen as one that produces the most spores, allowing the pathogen to spread or seed itself in many locations. Copious slime and mucus production and projectile vomiting and diarrhea were frequently suggested during discussions of the perfect pathogen. And it’s true that these features really get the attention of the infected person and her/his caregiver. There are some pretty scary microbial buggers out there, for instance those that cause hemolytic anemia and/or raging fevers; these are the attention getters of the infectious disease world.

To be honest, I don’t recall what the class decided was the perfect pathogen. But the criteria for a perfect pathogen stuck with me. A successful pathogen:

- Avoids the host immune system

- Is highly infective, spreading to multiple hosts and successfully infecting new individuals

- Has a relatively low mortality rate (rapid death of the host interferes with spread)

The perfect pathogen could be a bacterium or a virus.

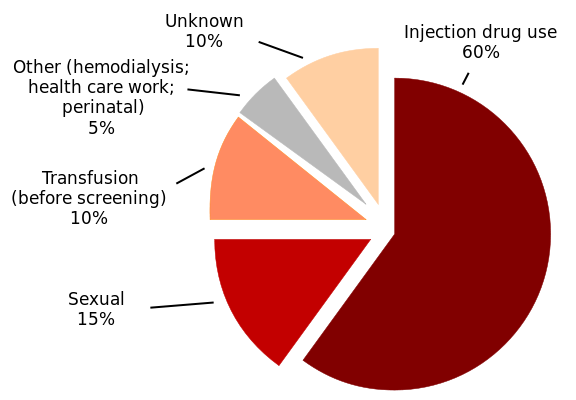

Hepatitis C virus is an excellent candidate for perfect pathogen. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive strand RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. Infection with HCV occurs when persons come into contact with blood from an infected person, such as when health care workers’ skin is pierced with a needle and blood from an infected individual, or when needles are shared with infected individuals.

Early or acute infection with HCV is either devoid of symptoms or characterized by mild, nondescript symptoms such as fatigue, fever, nausea, muscle and joint pain.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) ,

“Chronic HCV infection develops in 70%–85% of HCV-infected persons; 60%–70% of chronically infected persons have evidence of active liver disease. The majority of infected persons might not be aware of their infection because they are not clinically ill.”

It’s estimated that there are 130 million new cases of HCV infection annually, worldwide.

Here is a perfect pathogen criterion that was omitted above. HCV is dangerous not only because so many people are infected and infectious without knowing it, but because it is difficult to study. The only animal model that is fully susceptible to HCV is the chimpanzee. However, there are many legal and ethical, not to mention economical and practical reasons for not using chimpanzees for research. Those reasons also support of finding a small animal model for HCV infection.

There are successful cell culture systems for the study of HCV, but to learn about the pathogenesis of the disease, an animal model is needed.

Mice are naturally not susceptible to HCV. However, researchers recently reported a breakthough en route to an immune-competent mouse model for HCV infection in a Nature publication: ”Completion of the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle in genetically humanized mice”.

HCV infection requires two entry factors, the liver cell receptors CD81 and occludin. In this recent work, researchers developed transgenic mice that express these entry factors and whose innate immune system cannot block the virus from entry. These mice have sustained HCV infection for up to 11 weeks, with viral genomes detectable in both liver tissue and in serum. The viral infection was real—it could be blocked by neutralizing antibodies.

The authors also reported spenomegaly in these mice, with an increased frequency of NK- and B-cells, as well as liver infiltrates of CD8+ T-cells. Splenomegaly is a sign of antibody response to infection.

A cursory glance at these findings highlights the value of this mouse model in the study of HCV pathogenesis and, potentially, for development of T-cell activating vaccines.

However, these mice did, eventually, all clear the HCV, and so do not yet provide a model for chronic HCV infection.

There is a definite risk of longterm complications from HCV infection that is not treated. CDC has mounted a campaign to inform people of the risks of untreated hepatitis C virus infection, encouraging in particular that persons born between 1945-1965 get tested for Hepatitis C.

Liver disease, liver cancer and deaths from Hepatitis C are on the rise and treatment is available that can eliminate the virus and prevent liver damage. It is not known why “baby boomers” or persons born during this time have high rates of Hepatitis C. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, rates of Hepatitis C were highest. In addition, widespread testing of the blood supply was not in place until 1992.

Visit the CDC website or your healthcare provider for more information on Hepatitis C virus infection, testing and treatment.

It is possible that Hepatitis C virus was a perfect pathogen, but infected persons can beat the infection, especially with early treatment.

Reference

![]()

Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Donovan BM, Labitt RN, Budell WC, Friling T, Vogt A, Catanese MT, Satoh T, Kawai T, Akira S, Law M, Rice CM, Ploss (2013). Completion of the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle in genetically humanized mice Nature DOI: 10.3410/f.718056441.793481497