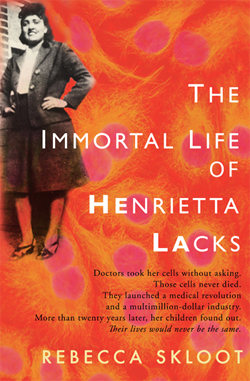

It’s been a while since I have pre-ordered a book and waited expectantly for its arrival. Ever since reading the first reviews of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, I have been itching to read this book for myself.

It’s been a while since I have pre-ordered a book and waited expectantly for its arrival. Ever since reading the first reviews of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, I have been itching to read this book for myself.

So, when I drove home and saw the boot prints in the snow leading to the front porch, I knew the awaited tome had finally arrived. I began my journey, guided by the able pen of Skloot, through the life of Henrietta Lacks and the incredible story of her tumor cells, first introduced to me as HeLa cells when I was a college student. At that time there was virtually no acknowledgment of the fact that these cells, a staple of cell biology research and teaching, originally came from a person, a mother, a wife, a daughter.

These blog entries will not attempt to be a review of Skloot’s book; more experienced book critics have done that and done it well. Instead, here is my reaction to the book “journaled” as I read—my thoughts and questions as a scientist, a writer, a woman, a mother, a daughter, and a member of the human race.

Entry 6 March 15, 2010

Then, in 1953, a geneticist in Texas accidentally mixed the wrong liquid with HeLa and a few other cells, and it turned out to be a fortunate mistake. The chromosomes inside the cells swelled and spread out, and for the first time, scientists could see each of them clearly. —Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Okay, Ms. Skloot, no fair teasing a geneticist reader like that. Who was the scientist in Texas? What was the wrong liquid? How long did it take for the scientist to realize he had launched the entire field of cytogenetics with his mistake?

Entry 5 March 7, 2010

“Helen Lane. Her name was Helen Lane, right? Even my wife said that is what she learned in school.”

My colleague turned to me questioningly, knowing I was reading the book.

“No, it was Henrietta Lacks, although Helen Lane was the name I was taught at one time as well.”

When it comes to science journalism, and frankly even science education, there is a lot of misinformation out there. Some of it is the fault of the journalists. Some of it is the fault of the scientists. Some of it is the fault of the readers, who don’t demand better work.

It was no different in 1953 than now. We need more careful journalists and more communicative scientists, and we need to get them talking to each other, and we need to get their conversations in front of an engaged and thinking public. But that’s another story.

Henrietta’s name was first botched in a Minneapolis Star article in 1953 when it was reported as Henrietta Lakes. Nobody knows if the reporter got it wrong or if the person who provided the name to the reporter got it wrong. But the article gave a name to a person and added human interest to the story of the HeLa cells.

A second article was written for Collier’s magazine, a publication with national circulation, with the conditional cooperation of the researchers at Hopkins: George Gey from Hopkins would have final review and approval over the story, and the story could not include Henrietta’s personal story or name.

When the story was published, the name of the patient was reported as “Helen L” and the story stated that the cells were grown from tissue “taken after her death”. Interestingly, those errors were not corrected by Gey and the head of public relations for Hopkins when they approved the article for publication.

Where the name “Helen Lane” came from is not known, but certainly it is the name that most students of biology and medicine of my generation recognize as being associated with HeLa cells.

You never stop learning or discovering that quite often there are things in your formal education that you need to unlearn.

Entry 4 February 25, 2010

As Rebecca Skloot describes her attempts to contact the Lacks family to learn Henrietta’s story, I suddenly feel like I am reading a mystery novel. No one is talking. Skloot ends up in the same Baltimore hotel, staring at the same B-R-O-M-O-S-E-L-T-Z-E-R sign as a journalist had 23 years earlier when he contacted the Lacks family for a Rolling Stone article about Henrietta. The scene is surreal film noir, a private detective alone on the road trying to find answers to questions only to keep running into dead ends.

People agree to speak to Skloot and then turn her away without explanation. They’ll meet her, but only contact her by pager. Folks keep referencing that “Cofield situation”, and as the author asks in her own text, I ask in my own mind: “Who’s Cofield?”

One woman brings her to the library and gets “the tape” from a skeptical librarian, takes her to a hair parlor, locks the door and admonishes Skloot, “Don’t you open this door for nothing or nobody but me, you hear? And don’t you miss nothing in that video—use that rewind button, watch it twice if you have to, but don’t you miss nothing.”

The video turns out to be a BBC documentary about Henrietta and her cells.

Then, just as suddenly, Skloot returns us to the grim reality of Henrietta’s last days and the autopsy, which was performed with permission of her husband, although saying that the autopsy was being performed because they wanted to “run tests that might help Henrietta and Day’s children some day” wasn’t exactly forthright. They did not inform the husband about the cells grown from her cancer. They did not tell him that cells from Henrietta had been flown across oceans to laboratories in Europe and Asia and even carried into the mountains of Chile. Nor did Gey and his colleagues reveal that the real purpose of the autopsy was to get more cell samples.

I find it ironic that the laws at the time insisted that the hospital obtain consent for the autopsy on the dead patient but not for taking tissue from the living patient. It would appear that the deceased had more rights than the living, at least in this case.

Entry 3 February 17, 2010

As I read I am struck by contrasts, and perhaps that is what Skloot intended. There is the contrast of the unpredictable and erratic genius of George Gey the Hopkins researcher working on cell culture whose ideas would be recorded on napkins or torn off bottle labels and his wife and co-worker Margaret, the methodical surgical nurse, whose training in sterile technique was every bit as important as Gey’s breakthrough roller-tube culturing technique.

There is the contrast of the excitement at the growth of the HeLa cells in the laboratory, doubling everyday, growing to fill as much space as the technician, Mary, would give them and the foreboding I have as a reader, knowing that those same cells were also growing “like crabgrass” in Henrietta’s body, eventually to kill her. Along with that there is the contrast of the doctors at the Hopkins clinic pronouncing Henrietta “cured” with confidence based on the best information they have available to them, when in reality, they have no clue what is happening inside her body.

But what struck me emotionally and brought me to tears was the description of Henrietta having to institutionalize her daughter Elise. As a mom I can’t imagine being separated from my daughter like that, and like Henrietta, a little part of me would die under the same circumstances. I cried along with Elise for that one day a week when she got to see her mother.

Skloot opens her book with the quote “We must not see any person as an abstraction. Instead, we must see in every person a universe with its own secrets, with its own treasures, with its on sources of anguish and with some measure of triumph.” –Elie Wiesel. Passages like the one about Elsie drive home the message of that quote. We would all do well to put that quote into practice everyday.

Entry 2 February 8, 2010

First Point Henrietta wasn’t the only person whose tissue was taken without her consent.

Henrietta Lacks was examined and diagnosed by Dr. Howard Jones. He and his boss, Richard Wesley TeLinde, had proposed a controversial theory (at the time) about cervical cancer that suggested that the “dangerous” invasive cancers began as “carcinoma in situ”, cancer cells that lay on the surface of the cervix but had not yet invaded the tissue. TeLinde thought if he could get the carcinoma in situ cells to grow in culture and become invasive, he could prove his point. To work on culturing cervical cancer cells, he enlisted the help of George Gey, head of tissue culture research at Hopkins. All of these physicians were genuinely concerned about saving lives, solving the problem of cancer, but while they worked diligently on the problem of cancer and saving thousand of women’s lives in the abstract, they didn’t “see” the individuals who came to them as patients.

“Like many doctors of his era, TeLinde often used patients from the public wards for research, usually without their knowledge.”

“Gey took any cells he could get his hands on—he called himself ‘the world’s most famous vulture, feeding on human specimens almost constantly’.”

“TeLinde began collecting samples from any woman who happened to walk into Hopkins with cervical cancer.”

All women in public wards, white and black, who were too poor to pay for health care contributed cells. There are many things that can define a “vulnerable population”: skin color, inability to read and write, inability to speak a particular language, cognitive impairment, physical disability, youth, or advanced age to name a few. Anytime we run roughshod over the rights of an individual because we deem them as less important than the ideal or goal we are trying to reach for society (or science), we are violating that person just as Henrietta Lacks was violated when her cells were taken without her permission.

Second Point Science has a bad habit of only highlighting the positive results.

“…everyone else in his lab saw Henrietta’s sample as something tedious—the latest of what felt like countless samples that scientists and lab technicians had been trying and failing to grow for years.”

So often science neglects the work that yields negative results, yet it is from “getting it wrong” over and over that we are able to make the incremental progress required to “get it right.” Often the work that yields results that don’t support our hypotheses (or, in this case produce cells that did not grow in culture) is overlooked, barely mentioned, much like those countless women who contributed (without their knowledge) the “countless samples” in the quote above. Their families will never know what they contributed or even that they did so.

Entry 1 February 3, 2010

Several things captured my attention this morning as I read the opening pages of this book, but one stood out in particular. Chapter 1 is preceded by words from Henerietta Lacks’ daughter, Deborah, in which she talks about being the daughter of “HeLa”. She acknowledges the good that has come from the research done on HeLa cells, expresses righteous and understandable anger at all of this being done without any knowledge of her mother or the immediate family, anger that money was made on technologies developed from research with HeLa cells, when HeLa’s children couldn’t even afford to go to the doctor, and just plain exhaustion at the fight of it all. Deborah concludes, and you can almost hear her sigh as you read the end of the passage, “I just want to know who my mother was.”

Almost without thinking, I wrote in the margin of the page: “Don’t we all?” I lost my mother a few years ago, and I, along with my siblings, have struggled with much the same question, trying to remember who our mother was, to etch indelibly in our minds the image of her that seems to be fading daily: squinting at out-of-focus 8mm films, searching for any saved letters or messages, coveting every rare photo. I have talked with friends who have also lost their moms, and they say the same thing. One even said that there really wasn’t much physical evidence left of her mother’s life, that the evidence of her mother was really in the memory and habits of the people she interacted with. While Deborah Lacks’ situation is unique: learning that cells from your deceased mother’s body have been propagated over and over until they would weigh nearly 50 million metric tons if collected in one place is unimaginable, her reaction to having lost her mother is universal. She wants to know who her mother was, to know more about her, to know what she would think, to know what her voice would sound like. Even 50 million metric tons of cells can’t answer those questions.

Michele Arduengo

Latest posts by Michele Arduengo (see all)

- An Unexpected Role for RNA Methylation in Mitosis Leads to New Understanding of Neurodevelopmental Disorders - March 27, 2025

- Unlocking the Secrets of ADP-Ribosylation with Arg-C Ultra Protease, a Key Enzyme for Studying Ester-Linked Protein Modifications - November 13, 2024

- Exploring the Respiratory Virus Landscape: Pre-Pandemic Data and Pandemic Preparedness - October 29, 2024