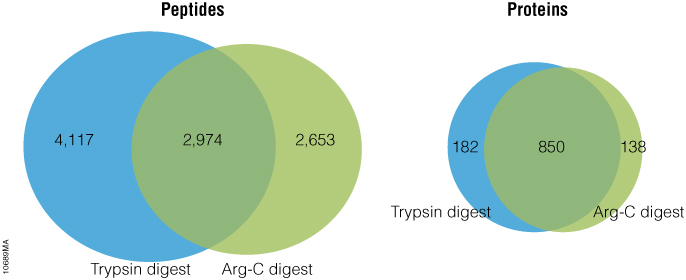

Arg-C (clostripain), Sequencing Grade (Cat.# V1881), is a specific endoproteinase isolated from the soil bacterium Clostridium histolyticum. It preferentially cleaves at the C-terminal side of arginine (R) residues. Unlike trypsin, Arg-C efficiently cleaves arginine sites followed by proline (P). This difference is important because every twentieth arginine is followed by proline. To illustrate this benefit, Arg-C was evaluated for protein analysis in two different experiments. In the first experiment, we studied the use of Arg-C for proteomic analysis. Yeast provides an excellent model proteome because its genome is well annotated. Yeast extract was digested in two parallel reactions, using trypsin in the first reaction and Arg-C in the second, using a conventional protocol consistent with LC-MS/MS analysis. As expected the trypsin digestion resulted in a high number of peptide and protein identifications (Figure 1). However, many peptides remained elusive. The parallel Arg-C digestion complemented the trypsin digestion by recovering an additional 2,653 peptides and providing a 37.4% increase in the number of identified peptides. Digesting with Arg-C also resulted in an increase in the number of identified proteins. In fact, 138 new proteins were identified in Arg-C digest compared to the parallel trypsin digest, offering a 13.4% increase in the overall number of identified proteins.

Are you looking for proteases to use in your research?

Explore our portfolio of proteases today.

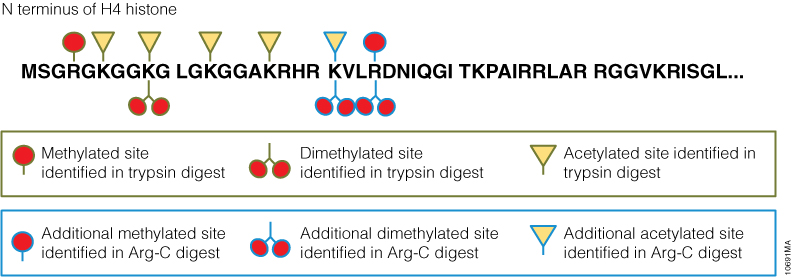

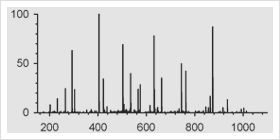

In a second experiment, the ability of Arg-C to analyze individual proteins was analyzed, selecting human histone H4 as a model protein. Like other histones, this protein is heavily modified post translational modifications (PTMs) that alter histone structure and regulate interaction with transcription factors. As a result, histone PTMs are implicated in gene regulation and associated with multiple disorders. Technical challenges, however, impede histone PTM analysis. Histone PTMs are complex and some, such as acetylation and methylation, prevent trypsin digestion, as shown by our data. In this experiment, trypsin digestion of histone H4 identified several PTMs (Figure 2). However, certain PTMs were missing. By digesting histone H4 with Arg-C, we were able to identify the missing PTMs including mono-, dimethylated and acetylated lysine and arginine residues. We speculate that the PTMs in human histone H4, which modified arginine and lysine residues, rendered trypsin unsuitable for preparing the corresponding histone regions for mass spectrometry. The problem was rectified by replacing trypsin with Arg-C.