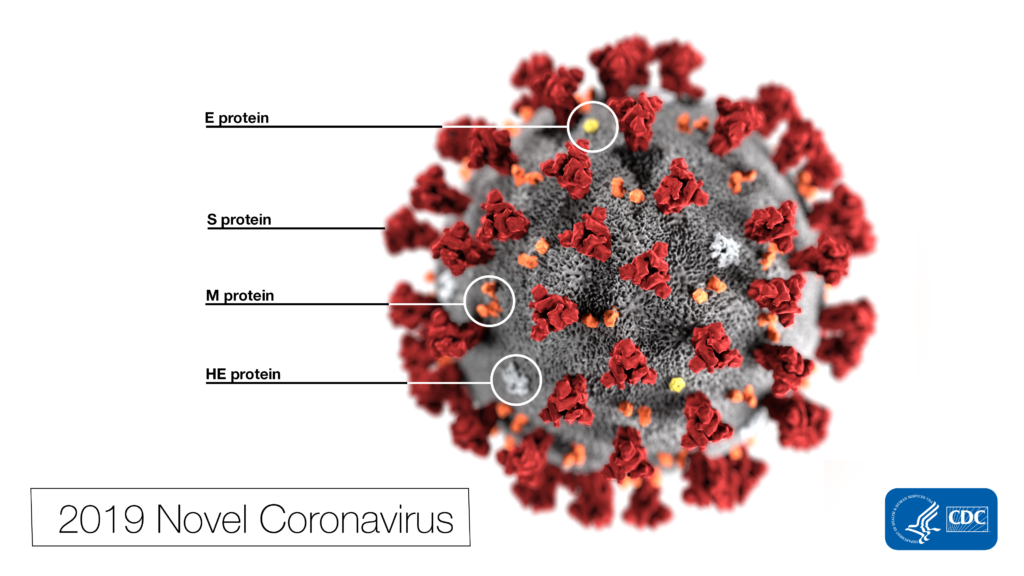

Remdesivir (RDV or GS-5734) was used in the treatment of the first case of the SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV ) in the United States (1). RDV is not an approved drug in any country but has been requested by a number of agencies worldwide to help combat the SARS-CoV-2 virus (2). RDV is an adenine nucleotide monophosphate analog demonstrated to inhibit Ebola virus replication (3). RDV is bioactivated to the triphosphate form within cells and acts as an alternative substrate for the replication-necessary RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). Incorporation of the analog results in early termination of the primer extension product resulting in the inhibition.

Why all the interest in RDV as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2 ? Much of the interest in RDV is due to a series of studies performed by collaborating groups at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (Ralph S. Baric’s lab) and Vanderbilit University Medical Center (Mark R. Denison’s lab) in collaboration with Gilead Sciences.

Continue reading “Investigation of Remdesivir as a Possible Treatment for SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV)”