The pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has brought the world to its knees. There have been many deaths, many persons with lingering disease (long COVID) and the inability to vaccinate everyone quickly, for starters. SARS-CoV-2 has not only been a tricky adversary in terms of treatment options to save lives, it’s also been a wily opponent to researchers studying the virus.

Contributing to the existing studies, with their review of the role of inflammasomes in COVID-19, Vora et al. recently published “Inflammasome activation at the crux of severe COVID-19” in Nature Reviews Immunology. In this paper they detail evidence of inflammasome activation and its role in SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Contributions of Those Lost in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic

I’d like to take a moment to note the uniquely awful nature of the virus at the center of this blog and the paper it reviews. Many of the papers we blog about describe research involving cell lines, mice or another animal model. The closest most reports get to human research subjects is the use of human cells lines. In the Vora et al. report, serum and tissue samples are from actual human patients, some that survived and many that did not survive COVID-19. It’s not lost on us, Dear Reader, the contributions of those that suffered and died due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Many persons with severe or fatal COVID-19 have made a significant contribution to our understanding of this virus and its treatment options. We owe them, as well as the researchers that have studied SARS-CoV-2, our sincerest gratitude.

Why the Interest in Inflammasomes?

For detailed information on inflammasomes you can read Ken’s blog, here. You will find background information there and on our inflammasome web page.

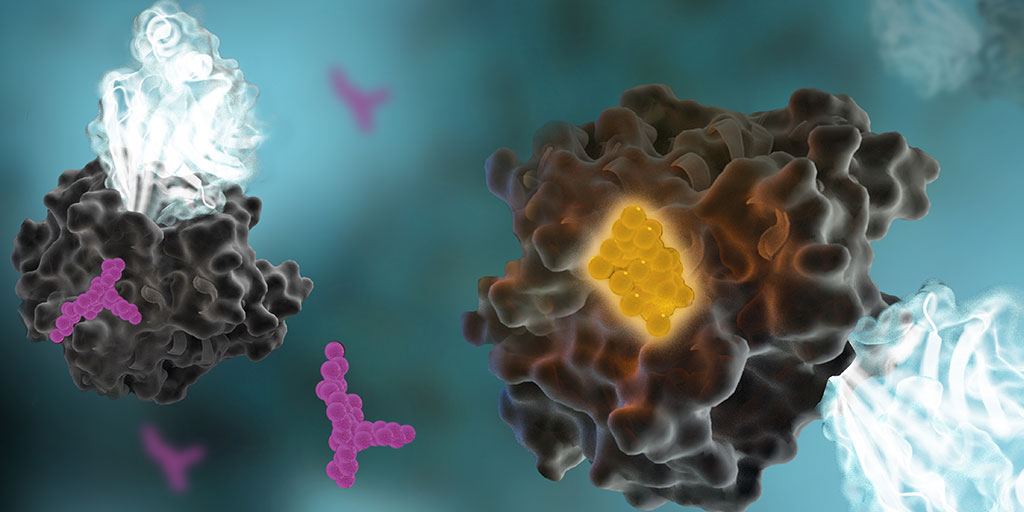

In their paper, Vora et al. provide evidence of inflammasome activation, both direct and indirect, in COVID-19. The authors note:

“Key to inflammation and innate immunity, inflammasomes are large, micrometrescale multiprotein cytosolic complexes that assemble in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and trigger proinflammatory cytokine release as well as pyroptosis, a proinflammatory lytic cell death.”

Continue reading “Evidence of Inflammasome Activation in Severe COVID-19” Like this:

Like Loading...