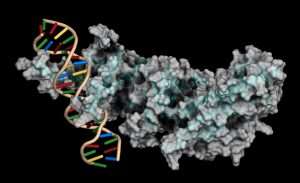

Protein-DNA interactions are fundamental processes in gene regulation in a living cells. These interactions affect a wide variety of cellular processes including DNA replication, repair, and recombination. In vivo methods such as chromatin immunoprecipitation (1) and in vitro electrophoretic mobility shift assays (2) have been used for several years in the characterization of protein-DNA interactions. However, these methods lack the throughput required for answering genome-wide questions and do not measure absolute binding affinities. To address these issues a recent publication (3) presented a high-throughput micro fluidic platform for Quantitative Protein Interaction with DNA (QPID). QPID is an microfluidic-based assay that cam perform up to 4096 parallel measurements on a single device.

The basic elements of each experiment includes oligonucleotides that were synthesized and hybridized to a Cy5-labeled primer and extended using Klenow. All transcription factors that were evaluated contained a 3’HIS and 5’ cMyc tag and were expressed in rabbit reticulocyte coupled transcription and translation reaction (TNT® Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate). Expressed proteins are loaded onto to the QIPD device and immobilized. In the DNA binding assay the fluorescent DNA oligonucleotides are incubated with the immobilized transcription factors and fluorescent images taken. To validate this concept the binding of four different transcription factor complexes to 32 oligonucleotides at 32 different concentrations was characterized in a single experiment. In a second application, the binding of ATF1 and ATF3 to 128 different DNA sequences at different concentrations were analyzed on a single device.

Literature Cited

- Ren, B. et al. (2007) Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA binding proteins. Science 316, 1497–502.

- Garner, M.M. (1981) A gel electrophoresis method for quantifying the binding of proteins to specific DNA regions. Nuc. Acids. Res. 9, 3047-60.

- Glick,Y et al. (2016) Integrated microfluidic approach for quantitative high throughput measurements of transcription factor binding affinities. Nuc. Acid Res. 44, e51.

![Bubonic plague victims in a mass grave in 18th century France. By S. Tzortzis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/Bubonic_plague_victims-mass_grave_in_Martigues%2C_France_1720-1721.jpg)

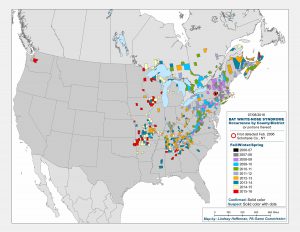

Honey bees are hard-working insects. Their pollination services are in such demand, humans tow hundreds of hives carrying millions of bees around in the back of semitrucks to bring honey bees to various locations such as California almond groves. Humans are also quite partial to the bee colony winter energy storage also known as honey. So while honey bees work hard to collect pollen and nectar from blooming plants and trees and store honey for the winter, humans insist on robbing the colony’s store of delicious sweetener for their own uses. Recent reports of high mortality in honey bee colonies has caused concern in many beekeepers who manage European honey bee apiaries for honey production and pollination services. These severe depletion of honey bee colonies have been attributed to the parasitic mite Varroa destructor in the colony, not only feeding off the larvae and pupae brooding in the colony but also transmitting viruses carried by the mite. Bee nutrition is important for the pollinators especially when overwintering in the hive. Without adequate nutrition, a colony may become weak and succumb to parasite or disease pressure, unable to survive until nectar and pollen are available in the spring. A study was recently published in PLOS ONE that examined how the landscape around Midwestern honeybee hives affected the ability of bees to overwinter and assessed their health by measuring levels of Varroa mites and honey bee viruses.

Honey bees are hard-working insects. Their pollination services are in such demand, humans tow hundreds of hives carrying millions of bees around in the back of semitrucks to bring honey bees to various locations such as California almond groves. Humans are also quite partial to the bee colony winter energy storage also known as honey. So while honey bees work hard to collect pollen and nectar from blooming plants and trees and store honey for the winter, humans insist on robbing the colony’s store of delicious sweetener for their own uses. Recent reports of high mortality in honey bee colonies has caused concern in many beekeepers who manage European honey bee apiaries for honey production and pollination services. These severe depletion of honey bee colonies have been attributed to the parasitic mite Varroa destructor in the colony, not only feeding off the larvae and pupae brooding in the colony but also transmitting viruses carried by the mite. Bee nutrition is important for the pollinators especially when overwintering in the hive. Without adequate nutrition, a colony may become weak and succumb to parasite or disease pressure, unable to survive until nectar and pollen are available in the spring. A study was recently published in PLOS ONE that examined how the landscape around Midwestern honeybee hives affected the ability of bees to overwinter and assessed their health by measuring levels of Varroa mites and honey bee viruses.