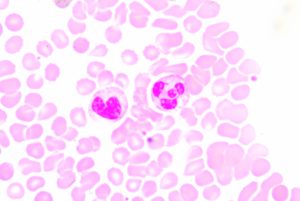

Back in 2015 the Ice Bucket Challenge brought Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) to public attention, initiating worldwide pleas for more funding of research toward a cure for this fatal disease, which is characterized by progressive degeneration of motor neurons. In spite of many efforts over the last few decades, the precise cause of ALS is still unknown.

Back in 2015 the Ice Bucket Challenge brought Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) to public attention, initiating worldwide pleas for more funding of research toward a cure for this fatal disease, which is characterized by progressive degeneration of motor neurons. In spite of many efforts over the last few decades, the precise cause of ALS is still unknown.

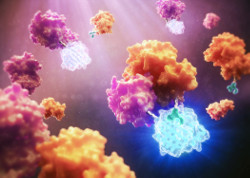

The complexity of the problem of ALS pathogenesis is highlighted in the review “Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism” published in Nature in November 2016. The review highlights a long list of genetic factors implicated in ALS, grouping them into genes affecting protein quality control, RNA stability/function, and the cytoskeletal structure of neuronal cells.

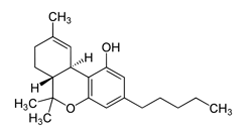

Mutations in the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD1) were the first to be associated with ALS. According to the review, more than 170 SOD1 mutations causing ALS have since been identified. Many of these mutations are thought to result in misfolding of SOD1, contributing to toxicity when the misfolded protein accumulates within the cell.

A paper by Oh-hashi et al., published in Cell Biochemistry and Function in October 2016 used the NanoBiT protein complementation assay to investigate the effect of two common ALS-associated SOD1 mutations on dimerization of the SOD1 protein. Continue reading “NanoBiT Assay Applied to Study Role of SOD1 in ALS”

fun now requires a bit of effort and prioritization. With the continual distractions of Netflix, social media and online news stories, it’s a challenge to find time to read books the way I once did.

fun now requires a bit of effort and prioritization. With the continual distractions of Netflix, social media and online news stories, it’s a challenge to find time to read books the way I once did.