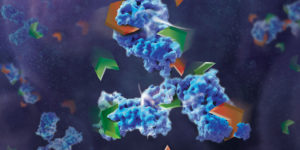

Several pharmaceutical companies have biosimilar versions of therapeutic mAbs in development. Biosimilars can promise significant cost savings for patients, but the unavoidable differences

between the original and thencopycat biologic raise questions regarding product interchangeability. Both innovator mAbs and biosimilars are heterogeneous populations of variants characterized by differences in glycosylation,oxidation, deamidation, glycation, and aggregation state. Their heterogeneity could potentially affect target protein binding through the F´ab domain, receptor binding through the Fc domain, and protein aggregation.

As more biosimilar mAbs gain regulatory approval, having clear framework for a rapid characterization of innovator and biosimilar products to identify clinically relevant differences is important. A recent reference (1) applied a comprehensive mass spectrometry (MS)-based strategy using bottom-up, middle-down, and intact strategies. These data were then integrated with ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and collision-induced unfolding (CIU) analyses, as well as data from select biophysical techniques and receptor binding assays to comprehensively evaluate biosimilarity between Remicade and Remsima.

The authors observed that the levels of oxidation, deamidation, and mutation of individual amino acids were remarkably similar. they found different levels of C-terminal truncation, soluble protein aggregates, and glycation that all likely have a limited clinical impact. Importantly, they identified more than 25 glycoforms for each product and observed glycoform population differences.

Overall the use of mass spectrometry-based analysis provides rapid and robust analytical information vital for biosimilar development. They demonstrated the utility of our multiple-attribute monitoring workflow using the model mAbs Remicade and Remsima and have provided a template for analysis of future mAb biosimilars.

1. Pisupati, K. et. al. (2017) A Multidimensional Analytical Comparison of Remicade and the Biosimilar Remsima. Anal. Chem 89, 38–46.

Like this:

Like Loading...