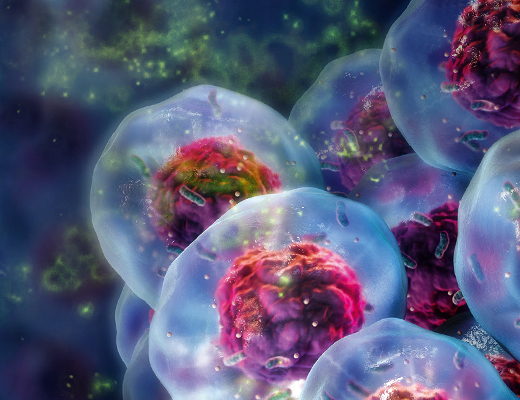

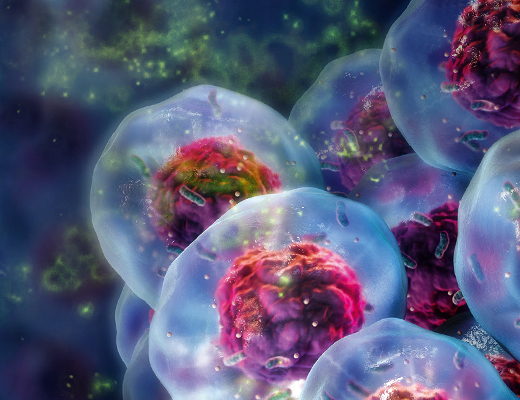

For a long time, the drug industry has relied on flat 2D cell cultures grown on a plate to screen for potential drugs. However, 2D models do not accurately reflect the native environment of cells in vivo. 3D cell cultures, on the other hand, better represent the numerous cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and hypoxic conditions that have a profound effect on the behavior of cells. In a 2018 study published in Oncogene, Kota et al. developed a high-throughput 3D spheroid-based screening assay to identify drug candidates that target RAS proteins.

For a long time, the drug industry has relied on flat 2D cell cultures grown on a plate to screen for potential drugs. However, 2D models do not accurately reflect the native environment of cells in vivo. 3D cell cultures, on the other hand, better represent the numerous cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and hypoxic conditions that have a profound effect on the behavior of cells. In a 2018 study published in Oncogene, Kota et al. developed a high-throughput 3D spheroid-based screening assay to identify drug candidates that target RAS proteins.

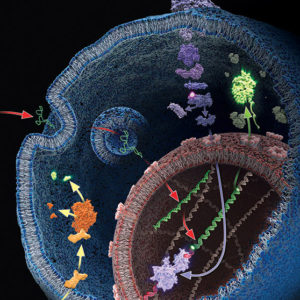

RAS proteins are GTPases that transmit extracellular signals into cellular signaling pathways, which could activate cell proliferation, differentiation and survival mechanisms. Oncogene mutation in the three human RAS genes (HRAS, NRAS and KRAS) are found in 30% of all cancers, making RAS proteins the most common oncogene. In fact, mutations in KRAS are found in >90% of pancreatic cancers. Despite the prevalence of RAS mutations, targeting RAS proteins with drugs is extremely challenging due to the complex nature of the protein.

The authors in this study wanted to test a new approach using a 3D spheroid-based screening assay to find drugs that target RAS proteins. They first harvested 2D monolayer cultures of pancreatic epithelial tumor cells that express either wild-type KRAS or mutant oncogenic KRAS, and tested their ability to form 3D spheroids. They confirmed spheroid growth using the CellTiter-Glo® 3D Cell Viability Assay with linearity of detection in the range of 1,000–10,000 cells seeded.

The 3D spheroids were then treated with a library of 1,280 known drugs. From the high-throughput screen, they identified one compound with the greatest selective inhibition against oncogenic KRAS. The compound is called Proscillaridin A, a cardiac glycoside that is known for treating congestive heart failure and cardiac arrhythmia. In 3D spheroids, Proscillardin A inhibited oncogenic KRAS at a >90% inhibition rate, with <10% inhibition of wild-type KRAS. In 2D cultures, however, there was no selective inhibition of oncogenic KRAS (inhibition rates for both oncogenic and wild-type KRAS were about 50%). This means that Proscillaridin A would not have been identified as a candidate if the screen was done using only 2D cultures.

Next, the authors wanted to determine how Proscillaridin A impacts tumor cell viability. Could it induce apoptosis in tumor cells? To test this, they used the RealTime-Glo™ Annexin V Apoptosis Assay. This bioluminescent assay is able to detect apoptosis in real time, based on the exposure of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane when apoptosis occurs. Using this assay, they found that Proscillaridin A induced apoptosis at earlier time points and higher rates in 3D spheroids expressing oncogenic KRAS compared with wild-type KRAS. In 2D cultures, there was no difference in the rate of apoptosis.

This study shows that high-throughput screening in 3D spheroids can identify potential drugs that would not have been discovered in a 2D format. This provides hope for finding drugs against difficult target proteins such as RAS.

Reference: Kota S., et al. (2018) A novel three-dimensional high-throughput screening approach identifies inducers of a mutant KRAS selective lethal phenotype. Oncogene. Epub ahead of print.

Like this:

Like Loading...

When someone is admitted to a hospital for an illness, the hope is that medical care and treatment will help them them feel better. However, nosocomial infections—infections acquired in a health-care setting—are becoming more prevalent and are associated with an increased mortality rate worldwide. This is largely due to the misuse of antibiotics, allowing some bacteria to become resistant. Furthermore, when an antibiotic wipes out the “good” bacteria that comprise the human microbiome, it leaves a patient vulnerable to opportunistic infections that take advantage of disruptions to the gut microbiota.

When someone is admitted to a hospital for an illness, the hope is that medical care and treatment will help them them feel better. However, nosocomial infections—infections acquired in a health-care setting—are becoming more prevalent and are associated with an increased mortality rate worldwide. This is largely due to the misuse of antibiotics, allowing some bacteria to become resistant. Furthermore, when an antibiotic wipes out the “good” bacteria that comprise the human microbiome, it leaves a patient vulnerable to opportunistic infections that take advantage of disruptions to the gut microbiota.

For a long time, the drug industry has relied on flat 2D cell cultures grown on a plate to screen for potential drugs. However, 2D models do not accurately reflect the native environment of cells in vivo. 3D cell cultures, on the other hand, better represent the numerous cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and hypoxic conditions that have a profound effect on the behavior of cells. In a 2018 study published in Oncogene, Kota et al. developed a high-throughput 3D spheroid-based screening assay to identify drug candidates that target RAS proteins.

For a long time, the drug industry has relied on flat 2D cell cultures grown on a plate to screen for potential drugs. However, 2D models do not accurately reflect the native environment of cells in vivo. 3D cell cultures, on the other hand, better represent the numerous cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and hypoxic conditions that have a profound effect on the behavior of cells. In a 2018 study published in Oncogene, Kota et al. developed a high-throughput 3D spheroid-based screening assay to identify drug candidates that target RAS proteins.