This series of blogs about Quantitation for NGS is written by guest blogger Adam Blatter, Product Specialist in Integrated Solutions at Promega.

This series of blogs about Quantitation for NGS is written by guest blogger Adam Blatter, Product Specialist in Integrated Solutions at Promega.

As sequencing technology races toward ever cheaper, faster and more accurate ways to read entire genomes, we find ourselves able to study biological systems at a level never before possible. From basic science to translational research, massively parallel sequencing (also known as next-generation sequencing or NGS) has opened up new avenues of inquiry in genomics, oncology and ecology.

Many commercial sequencing platforms have been established (e.g., Illumina, IonTorrent, 454, PacBio), and new technologies are developed every day to enable new and unique applications. However, all of these platforms and technologies work off the same general principle: nucleic acid must be extracted from a sample, arranged into platform-specific library constructs, and loaded into the sequencer. Regardless of the sample type or the platform used, every step throughout this workflow is critical for successful results. An often overlooked part of the NGS workflow is sample quantitation. Here we are presenting the first in a series of four short blogs about the critical step of quantitation in NGS workflows.

Sample input is critical to NGS in terms of both quality and quantity. Knowing how much DNA you have, often in nanogram quantities, can make the difference between success and failure. There are several key points in the NGS workflow where sample quantitation is important before you can proceed:

- After initial nucleic acid extraction from the sample matrix and before proceeding with library preparation

- Post-library preparation when pooling barcoded libraries for multiplexing

- Final pooled library quantitation immediately before loading for sequencing

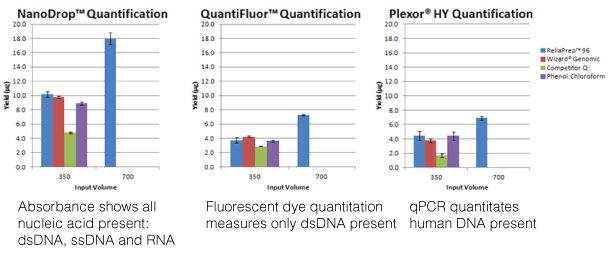

There are several common methods for quantitating nucleic acids: UV-spectroscopy, Fluorescence spectoscopy, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). Because of inherent differences in sensitivity, specificity, time and cost, each of these techniques pose certain advantages and disadvantages with respect to the specific sample you are quantitating. Our next three blogs will discuss each of these methods against the backdrop of quantitating samples for NGS applications.

Read Part 2: Nucleic Acid Quantitation by UV Absorbance: Not for NGS

Read Part 3: Fluorescence Dye-Based Quantitation: Sensitive and Specific for NGS Applications

Read Part 4: Real-Time (Quantitative) qPCR for Quantitating Library Prep before NGS