The Brazilian state of Amazonas experienced two distinct waves of COVID-19 infections in 2020. After the first wave, a team from the University of Sao Paolo projected that the city of Manaus would reach the theoretical threshold for herd immunity by the end of the summer. However, a second COVID-19 wave erupted in December 2020, coinciding with the rise of Variant of Concern (VOC) P.1.

New research published in Nature Medicine examined the different lineages of COVID-19 present in Brazil over time and determined that the two waves were driven by different variants. The first wave was driven by the variant B.1.195, which was imported from Europe in the spring. The second wave was largely driven by VOC P.1. The Nature Medicine study is the first to use viral sequences from samples collected throughout 2020 to explore the epidemiological and virological factors behind the two distinct COVID-19 waves.

Detecting VOC P.1 in Amazonas Samples

The researchers started by generating whole-genome sequences of 250 SARS-CoV-2 samples collected between March 2020 and January 2021. The survey showed that 20% of the sequences belonged to the B.1.195 lineage, and these mostly corresponded with the first exponential growth phase. 24% of the samples belonged to the P.1 lineage, and all of these samples corresponded with the rise of the second exponential growth phase. The largest share belonged to B.1.1.28 (37%), which replaced B.1.195 as the dominant variant in Brazil shortly after the first wave until the rise of VOC P.1.

The team also used real-time RT-PCR to analyze 1,232 positive samples collected in Amazonas between November 1, 2020 and January 21, 2021. The assay was designed to detect a deletion in NSP6, which is a signature mutation of VOC P.1. None of the samples collected before December 16 showed the NSP6 deletion, but it was common in samples starting in mid-December. Combining the two analysis methods, the team found the P.1 lineage in 0% of samples collected in November 2020, but by January 1-15 it was present in 73.8% of samples.

This data supports the theory that VOC P.1 first emerged in December 2020 and was the dominant lineage driving the second wave in Amazonas.

Two COVID-19 Waves: Virological and Epidemiological Factors

In addition to tracking the prevalence of lineages throughout the pandemic, the researchers also offered suggestions for how Amazonas experienced two distinct waves of COVID-19 infections.

Using computer modeling, the team found a significant reduction in reproductive efficiency (Re) of lineages B.1.195 and B.1.1.28 in April-May 2020, around the same time that Amazonas increased social distancing measures. Transmission rates remained low until the interventions were relaxed in September 2020. This suggests that the reduction in cases was not a result of herd immunity. Instead, nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPI) limited the first wave and contained the spread through the summer.

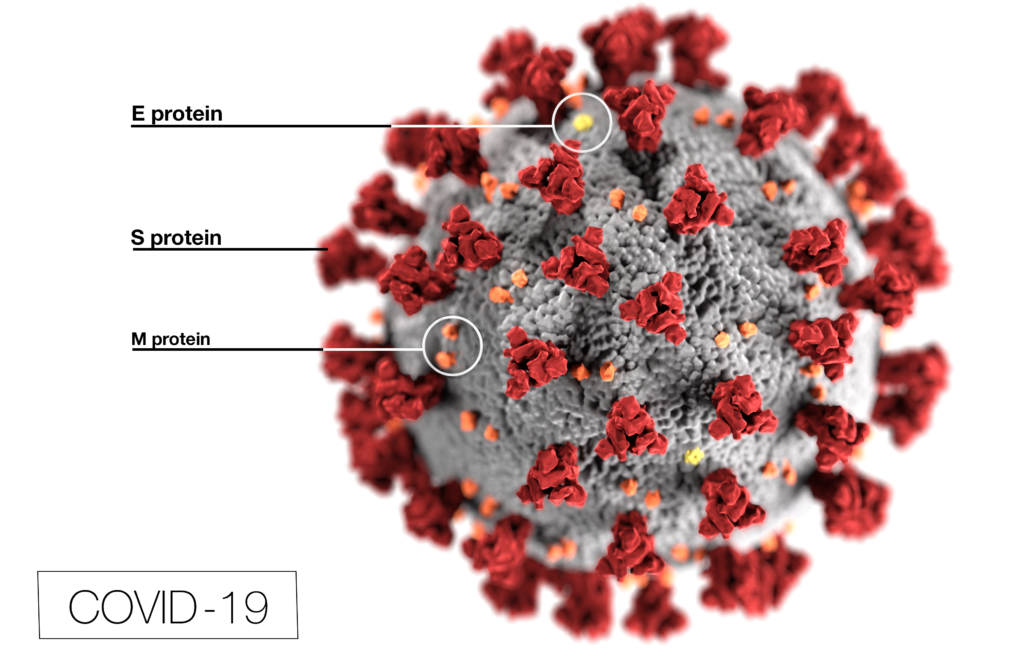

Using real-time RT-PCR, the researchers found that the viral load of P.1 infections was nearly ten times the viral load of non-P.1 infection. They also referenced other research that found that VOC P.1 has a stronger affinity for the human receptor ACE2 than B.1.195 and B.1.1.28. P.1 is clearly a highly transmissible VOC, and it evolved in an ideal environment for rapid spread. Amazonas had relaxed social distancing measures by late 2020, P.1 was able to quickly reach extremely high infection rates.

The study did not directly address theories that P.1 evades immunity developed from prior infections, but they concluded that a combination of epidemiological and virological factors allowed P.1 to drive a second wave of COVID-19 in Amazonas starting in December.

The paper includes a supplementary note suggesting that NPIs instituted in Manaus in January 2021 significantly reduced transmission rates of VOC P.1. The team ends the paper by reiterating the importance of adequate social distancing measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 and prevent the emergence of new Variants of Concern.

Read the entire paper here.

This study used the Maxwell® RSC Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit to extract viral RNA from samples. Learn more about the kit and its uses during the COVID-19 pandemic here.