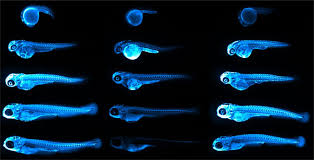

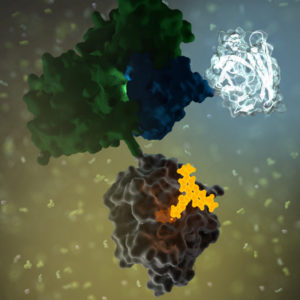

Credit: Figure 5.D of The LipoGlo reporter system for sensitive and specific monitoring of atherogenic lipoproteins by James Thierer, Stephen C. Ekker and Steven A. Farber.

Article licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Cardiovascular diseases, or CVDs, are collectively the most notorious gang of cold-blooded killers threatening human lives today. These unforgiving villains, including the likes of coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and pulmonary embolisms, are jointly responsible for more deaths per year than any other source, securing their seat as the number one cause of human mortality on a global scale.

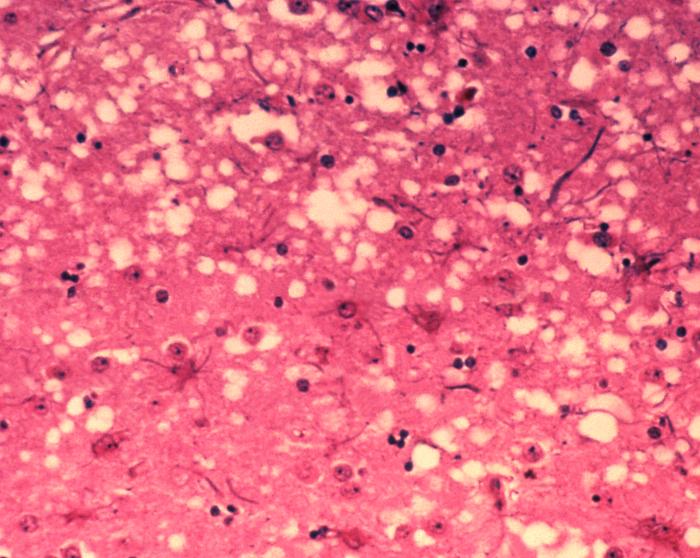

One of the trademarks of most CVDs is the thickening and stiffening of the arteries, a condition known as atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is characterized by the accumulation of cholesterol, fats and other substances, which together form plaques in and on the artery walls. These plaques clog or narrow your arteries until they completely block the flow of blood, and can no longer supply sufficient blood to your tissues and organs. Or the plaques can burst, setting off a disastrous chain reaction that begins with a blood clot, and often ends with a heart attack or stroke.

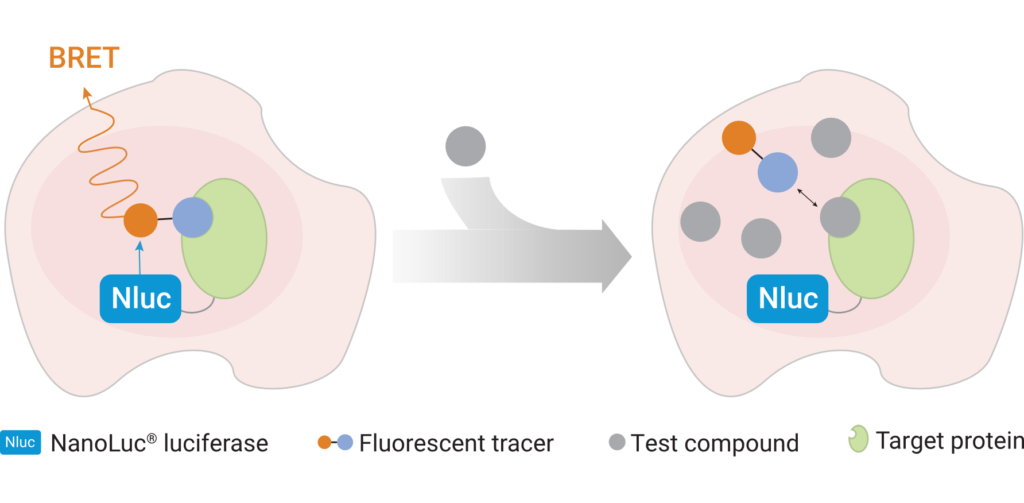

Given the global prevalence and magnitude of this problem, there is a significant and urgent demand for better ways to treat CVDs. In a recent study published in Nature Communications, researchers at the Carnegie Institution for Science, Johns Hopkins University and Mayo Clinic are taking the fight to CVDs through the study of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), the particles responsible for shuttling bad cholesterol throughout the bloodstream.

Continue reading “Striking Fear into the Heart of Cardiovascular Disease Using Zebrafish and NanoLuc® Luciferase”

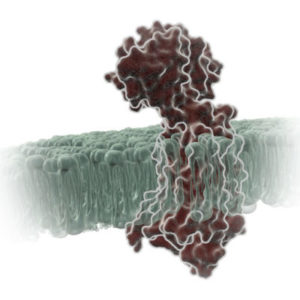

GPCRs

GPCRs