Identifying Inflammasome Inhibitors: What’s Missing

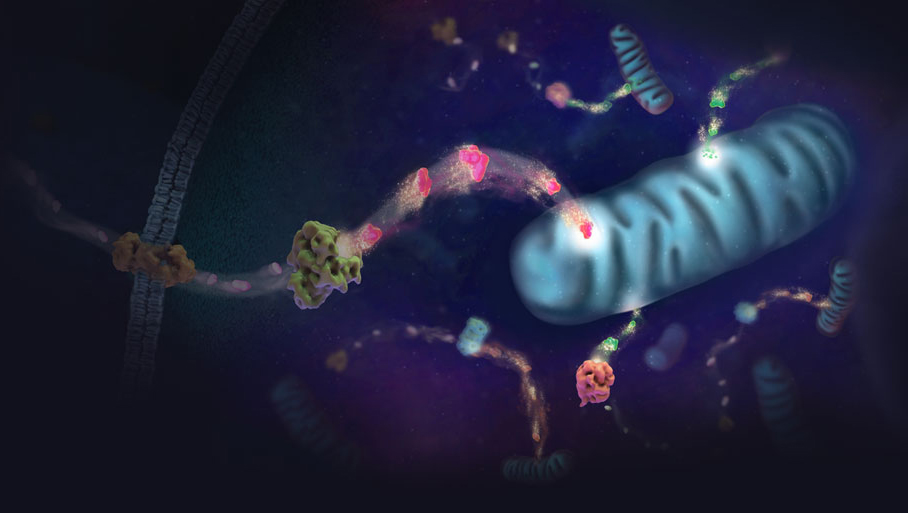

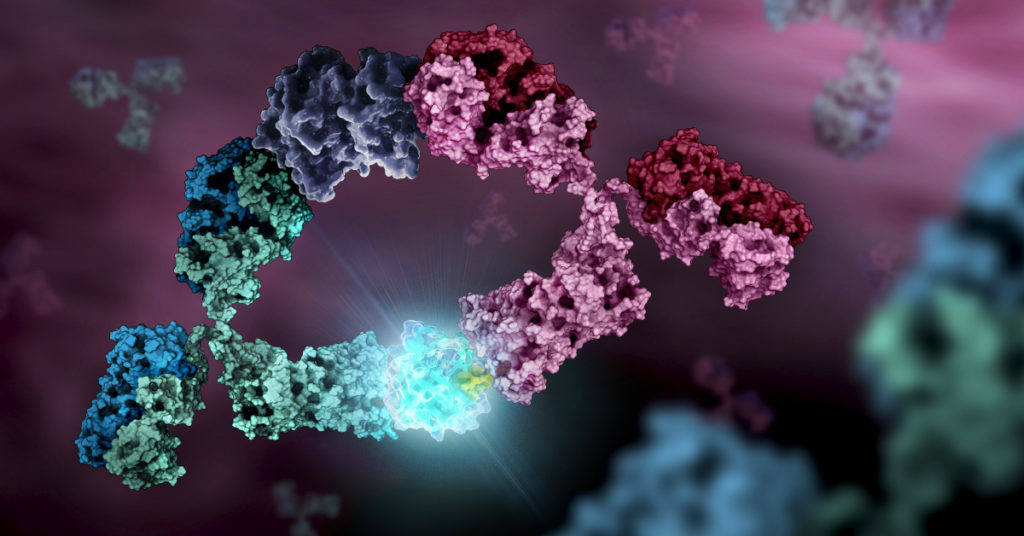

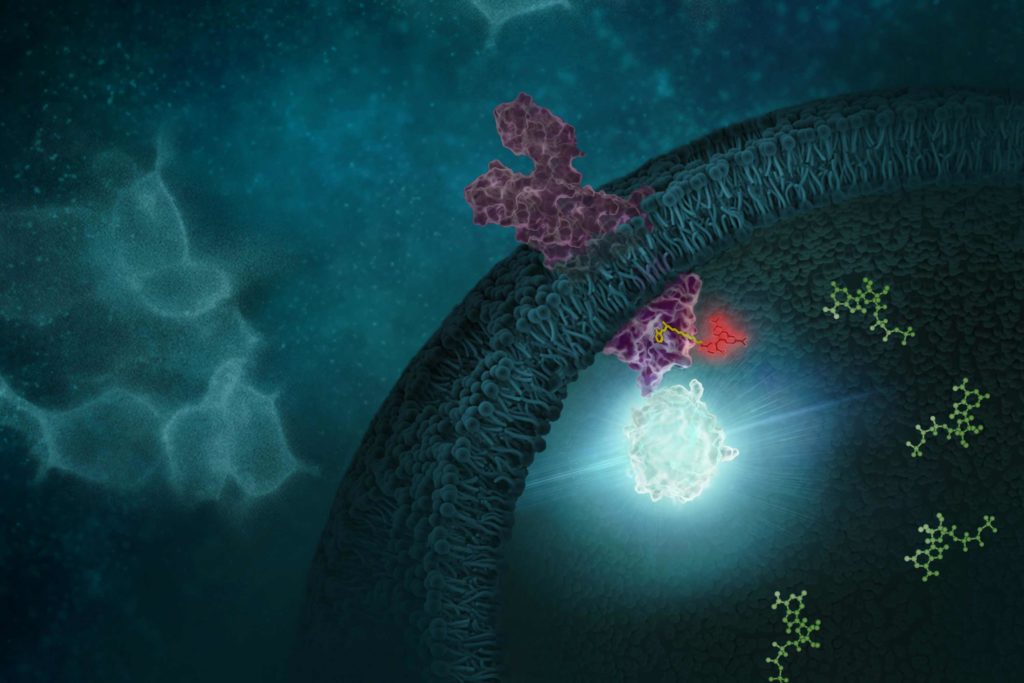

The NLRP3 inflammasome is implicated in a wide range of diseases. The ability to inhibit this protein complex could provide more precise, targeted relief to inflammatory disease sufferers than current broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory compounds, potentially without side effects.

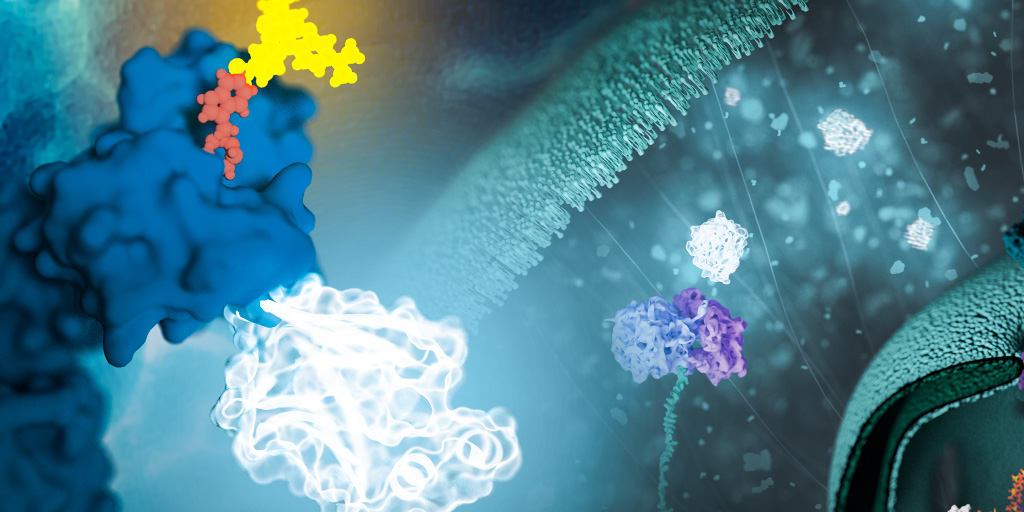

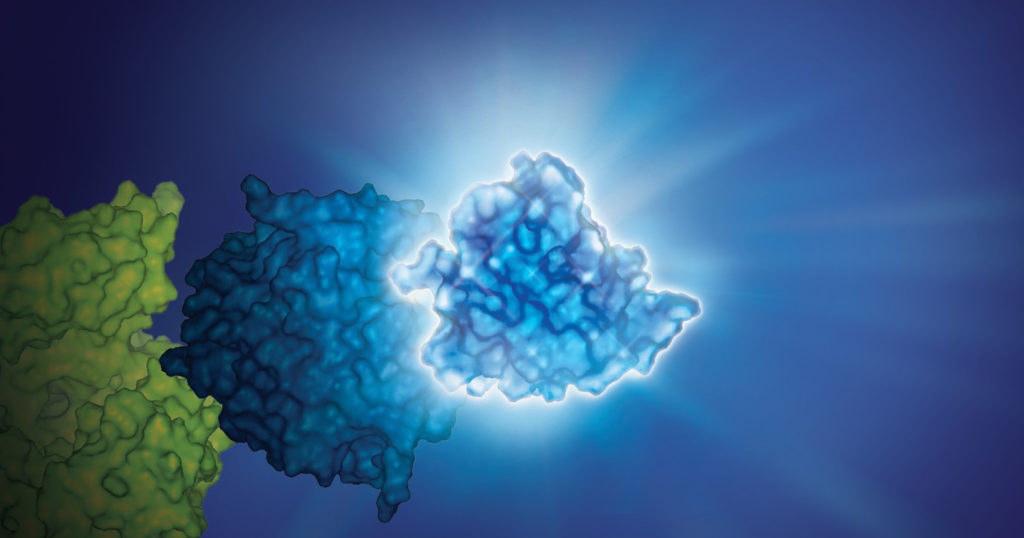

Studies of NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors have relied on cell-free assays using purified NLRP3. But cell-free assays cannot assess physical engagement of the inhibitor and target in the cellular micro-environment. Cell-free assays cannot show if an NLRP3 inhibitor enters the cell, binds the target and how long the inhibitor binding lasts.

Cell-based assays that interrogate the physical interaction of the NLRP3 target and inhibitor inside cells are needed.

Continue reading “Cell-Based Target Engagement and Functional Assays for NLRP3 Inhibitor Profiling Help Identify Successes and Failures”