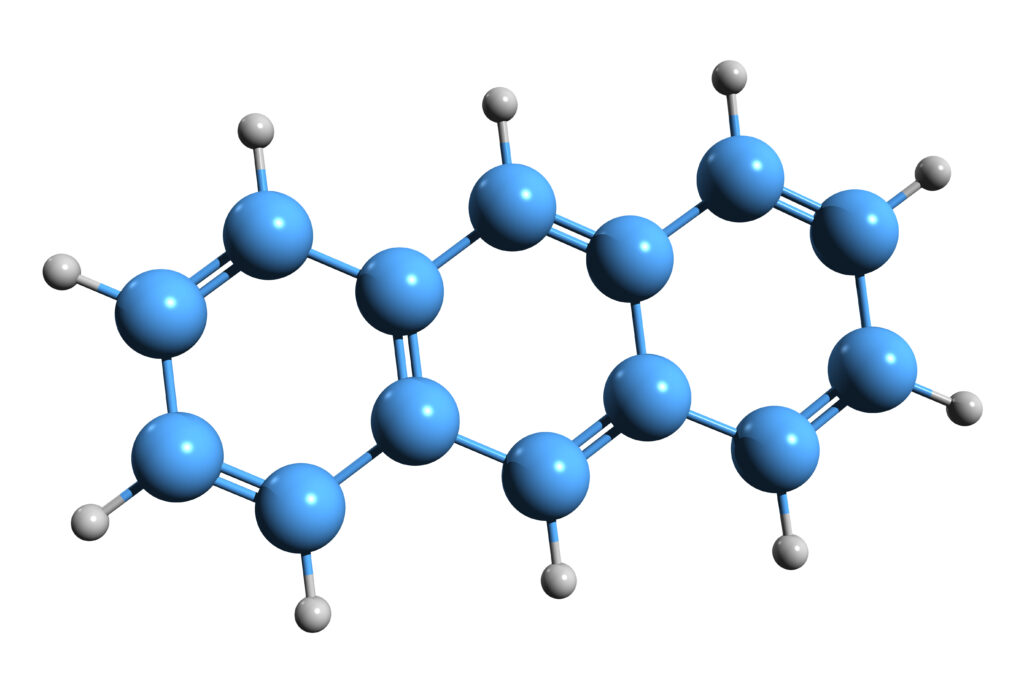

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are widespread environmental pollutants found in industrial waste, fossil fuel combustion and creosote-treated wood, to name a few. Due to these industrial activities, there are multiple pathways for human exposure. These compounds pose significant health risks due to their carcinogenic, teratogenic and mutagenic properties yet removing them from contaminated sites remains a challenge. Traditional remediation techniques, such as dredging and chemical treatment, are costly and can further disrupt ecosystems (1).

Mycoremediation—using fungi to break down pollutants into intermediates with lower environmental burden—offers a sustainable, low-cost alternative for PAH degradation. While past research focused on basidiomycete fungi like white rot fungi, these have been unreliable in large-scale field applications. This study investigates an alternative approach: leveraging naturally occurring ascomycete fungi from creosote-contaminated sediments to enhance PAH degradation (1).

The Problem: PAHs Are Persistent and Difficult to Remove

PAHs—a class of over 100 chemical compounds—are chemically stable and hydrophobic, meaning they bind tightly to soil and sediments, limiting bioavailability and making bacterial degradation inefficient. While some bacterial species can break down PAHs, they require direct cellular uptake, which is inefficient for high-molecular-weight PAHs that are not easily absorbed. Fungi, on the other hand, secrete extracellular enzymes that can oxidize and degrade PAHs without requiring cellular uptake, making them a promising alternative for bioremediation (1). Given these advantages, researchers hypothesized that native ascomycete fungi from contaminated environments might be better suited for PAH degradation than the previously studied basidiomycetes.

The Breakthrough: Identifying and Stimulating PAH-Degrading Fungi

Step 1: Isolating Native Fungal Strains

To find fungi naturally adapted to PAH degradation, researchers collected soil and root samples from creosote-contaminated sediments in the Elizabeth River, Virginia. A total of 132 fungal isolates were identified, with the majority belonging to Ascomycota phylum, rather than the traditionally studied Basidiomycota (1).

But how did they determine which fungi could break down PAHs?

- Screening for Key Enzymes: Fungal isolates were tested for laccase and manganese peroxidase (MnP) production, enzymes known to oxidize and degrade PAHs (1).

- Testing PAH Degradation: Isolates were incubated with model PAHs, fluoranthene, phenanthrene, pyrene, and benzo(a)pyrene, and researchers measured degradation efficiency in order to identify the most promising strains (1).

- Validating Genetic Identity: Using Promega’s GoTaq® Green Master Mix, researchers amplified ITS1-5.8-ITS2 ribosomal DNA to confirm which fungal strains were most effective at PAH degradation (1).

So, what does all of this mean?

By identifying native fungi that already thrive in contaminated environments, researchers eliminated the need for external inoculation and focused on fungi naturally suited for bioremediation. This provides a more efficient and sustainable route.

Step 2: Boosting Fungal PAH Degradation with Biostimulation

Simply identifying fungi capable of PAH degradation was not enough— researchers wanted to see if they could modify the existing environment to increase enzymatic activity, a process called biostimulation (1).

How did they do this? They introduced organic amendments to fungal cultures, designed to mimic natural nutrient sources and promote enzyme production. These included:

- Chicken feathers (keratin-based): Supports enzyme production via nitrogen supply (1).

- Wheat seeds (starch-based): Provides a general carbon source to stimulate fungal metabolism (1).

- Maple sawdust (lignin-based): Supports lignin-degrading enzyme production (1).

- Grasshoppers (chitin-based): Triggers laccase enzyme upregulation, boosting PAH degradation (1).

What Did They Find?

- The grasshopper amendment (rich in chitin) had the most significant effect, increasing laccase production by 18.9% in Paraphaeosphaeria isolates (1).

- Other fungal species also responded, with Septoriella and Trichoderma isolates significantly improving PAH removal after exposure to the grasshopper amendment (1).

These findings suggest that biostimulation using chitin-rich amendments may provide a low-cost, scalable approach to enhance fungal PAH degradation in contaminated environments.

Step 3: Measuring PAH Degradation Efficiency

To test whether biostimulated fungi could break down PAHs more effectively, researchers measured PAH removal rates before and after exposure to biostimulants (1).

The grasshopper amendment had the strongest effect, particularly on the following fungi (1):

- Septoriella sp. increased degradation of:

- Fluoranthene by 44%

- Pyrene by 54.2%

- Benzo(a)pyrene by 48.7%

- Trichoderma sp. saw a 58.3% increase in benzo(a)pyrene removal (1).

These results highlight the role of chitin as a metabolic trigger, providing a promising, cost-effective approach for bioremediation.

Why This Matters Summary:

- More Effective Fungal Bioremediation: This study highlights the potential of native ascomycetes, which may outperform basidiomycetes in real-world conditions, for use in PAH degradation.

- Biostimulation Enhances Enzyme Activity: Using natural amendments like grasshoppers to upregulate fungal enzymes could offer a low-cost, scalable solution for PAH cleanup.

- Broader Environmental Applications: If replicable at scale, these findings could extend to other contaminants and ecosystems, further advancing fungi-based environmental remediation strategies and reduce reliance on chemical treatments.

By shifting focus from basidiomycete fungi to ascomycete fungi and leveraging biostimulation strategies, researchers have identified a promising new approach for PAH cleanup. Could fungi hold the key to sustainable environmental restoration?

Reference:

- Crittenden, J., Raudabaugh, D., & Gunsch, C. K. (2025). Isolation, characterization, and mycostimulation of fungi for the degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at a superfund site. Biodegradation, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-024-10106-0