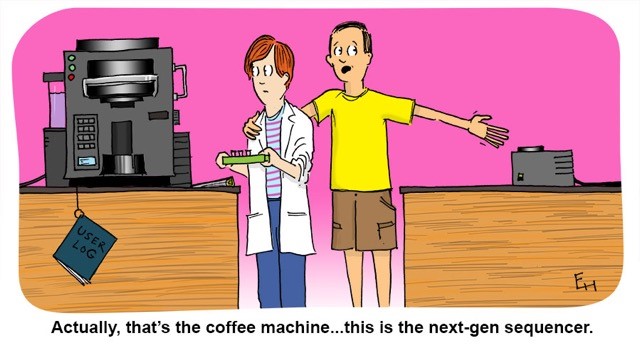

Forensic analysts have long sought precision when determining time of death. While on crime scene investigation television shows, the presence of insects always seems to reveal when a person died, there are many elements to account for, and the probable date may still not be accurate. Insects arrive days after death if at all (e.g., if the body is found indoors or after burial), and the stage of insect activity is influenced by temperature, weather conditions, seasonal variation, geographic location and other factors. All this makes it difficult to estimate the postmortem interval (PMI) of a body discovered an unknown time after death. One way to make estimating PMI less subjective would be to have calibrated molecular markers that are easy to sample and are not altered by environmental variabilities.

Bacterial communities called microbiomes have been frequently in the news. The influence of these microbes encompass living creatures and the environment. Not surprisingly, research has focused on the influence of microbiomes on humans. For example, changes in gut microbiome seem to affect human health. Intriguingly, microbiomes may also be a key to determining time of death. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has funded several projects focused on the forensic applications of microbiomes. One focus involves the necrobiome, the community of organisms found on or around decomposing remains. These microbes could be used as an indicator of PMI when investigating human remains. Recent research published in PLOS ONE examined the bacterial communities found in human ears and noses after death and how they changed over time. The researchers were interested in developing an algorithm using the data they collected to estimate of time of death.

Continue reading “Revealing Time of Death: The Microbiome Edition”

![Bubonic plague victims in a mass grave in 18th century France. By S. Tzortzis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/Bubonic_plague_victims-mass_grave_in_Martigues%2C_France_1720-1721.jpg)

Honey bees are hard-working insects. Their pollination services are in such demand, humans tow hundreds of hives carrying millions of bees around in the back of semitrucks to bring honey bees to various locations such as California almond groves. Humans are also quite partial to the bee colony winter energy storage also known as honey. So while honey bees work hard to collect pollen and nectar from blooming plants and trees and store honey for the winter, humans insist on robbing the colony’s store of delicious sweetener for their own uses. Recent reports of high mortality in honey bee colonies has caused concern in many beekeepers who manage European honey bee apiaries for honey production and pollination services. These severe depletion of honey bee colonies have been attributed to the parasitic mite Varroa destructor in the colony, not only feeding off the larvae and pupae brooding in the colony but also transmitting viruses carried by the mite. Bee nutrition is important for the pollinators especially when overwintering in the hive. Without adequate nutrition, a colony may become weak and succumb to parasite or disease pressure, unable to survive until nectar and pollen are available in the spring. A study was recently published in PLOS ONE that examined how the landscape around Midwestern honeybee hives affected the ability of bees to overwinter and assessed their health by measuring levels of Varroa mites and honey bee viruses.

Honey bees are hard-working insects. Their pollination services are in such demand, humans tow hundreds of hives carrying millions of bees around in the back of semitrucks to bring honey bees to various locations such as California almond groves. Humans are also quite partial to the bee colony winter energy storage also known as honey. So while honey bees work hard to collect pollen and nectar from blooming plants and trees and store honey for the winter, humans insist on robbing the colony’s store of delicious sweetener for their own uses. Recent reports of high mortality in honey bee colonies has caused concern in many beekeepers who manage European honey bee apiaries for honey production and pollination services. These severe depletion of honey bee colonies have been attributed to the parasitic mite Varroa destructor in the colony, not only feeding off the larvae and pupae brooding in the colony but also transmitting viruses carried by the mite. Bee nutrition is important for the pollinators especially when overwintering in the hive. Without adequate nutrition, a colony may become weak and succumb to parasite or disease pressure, unable to survive until nectar and pollen are available in the spring. A study was recently published in PLOS ONE that examined how the landscape around Midwestern honeybee hives affected the ability of bees to overwinter and assessed their health by measuring levels of Varroa mites and honey bee viruses.