On June 15, 2023, we announced the winners of the 2023 Promega iGEM grant. Sixty-five teams submitted applications prior to the deadline with projects ranging from creating a biosensor to detect water pollution to solving limitations for CAR-T therapy in solid tumors. The teams are asking tough questions and providing thoughtful answers as they work to tackle global problems with synthetic biology solutions. Unfortunately, we could only award nine grants. Below are summaries of the problems this year’s Promega grant winners are addressing.

UCSC iGEM

The UCSC iGEM team from the University of California–Santa Cruz is seeking a solution to mitigate the harmful algal blooms caused by Microcystis aeruginosa in Pinto Lake, which is located in the center of a disadvantaged community and is a water source for crop irrigation. By engineering an organism to produce microcystin degrading enzymes found in certain Sphingopyxis bacteria, the goal is to reduce microcystin toxin levels in the water. The project involves isolating the genes of interest, testing their efficacy in E. coli, evaluating enzyme production and product degradation, and ultimately transforming all three genes into a single organism. The approach of in-situ enzyme production offers a potential solution without introducing modified organisms into the environment, as the enzymes naturally degrade over time.

IISc-Bengaluru

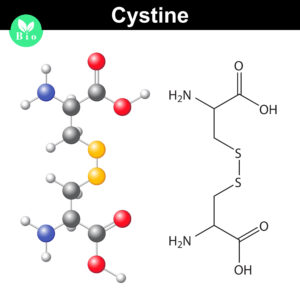

Endometriosis is a condition that affects roughly 190 million (10%) women of reproductive age worldwide. Currently, there is no treatment for endometriosis except surgery and hormonal therapy, and both approaches have limitations. The IISc-Bengaluru team at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, India, received 2023 Promega iGEM grant support to investigate the inflammatory nature of endometriosis by targeting IL-8 (interleukin-8) a cytokine. Research by other groups has snow that targeting IL-8 can reduce endometriotic tissue. This team will be attempting to create an mRNA vaccine to introduce mRNA for antibody against IL-8 into affected tissue. The team is devising a new delivery mechanism using aptides to maximize the delivery of the vaccine to the affected tissues.

Continue reading “2023 Promega iGEM Grant Winners: Tackling Global Problems with Synthetic Biology Solutions”