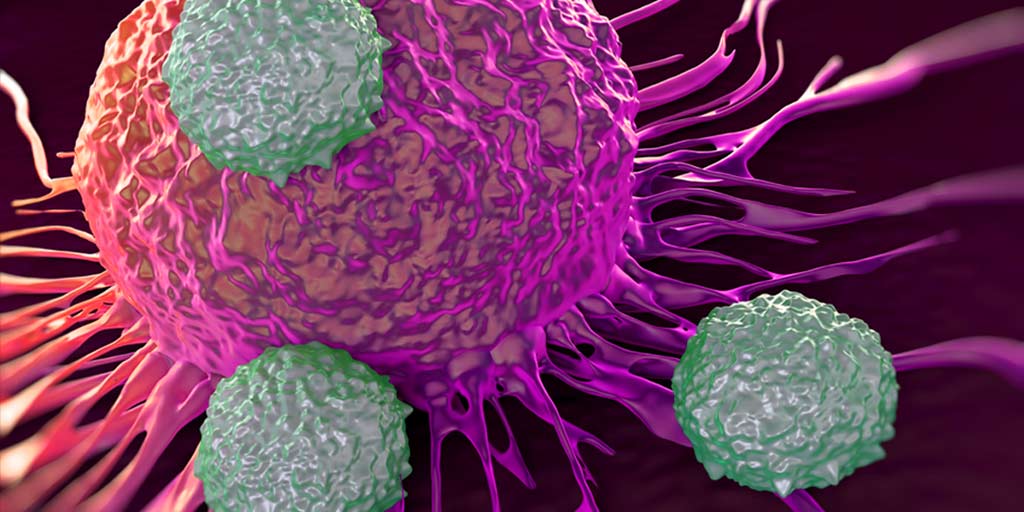

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), or immune checkpoint blockade, therapies are a revolutionary, and relatively new, approach to treating cancer. These therapies work by blocking immune checkpoint proteins that act to negatively regulate the immune system through the PD-1 pathway. Some tumors express immune checkpoints to prevent the immune system from producing a strong enough immune response to kill the cancer cells. When these checkpoint proteins are blocked by an ICI, the body’s T-cells can recognize and kill the cancer cells. ICI therapies show tremendous promise. Unfortunately, not all tumors express immune checkpoint proteins, and so, not all tumors will be effectively treated with ICI therapies. The challenge is differentiating between the tumors that will respond and tumors that won’t.

DNA Mismatch Repair Deficiency Status as Detected by Microsatellite Instability or Immunohisotchemistry are Important Biomarkers for ICI

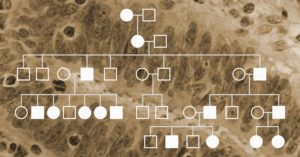

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of a clinical condition that can be found in tissue, blood, or other fluids. Predictive biomarkers for ICIs can help determine if these therapies are a suitable choice for treatment. Some tumors have deficiencies in their DNA mismatch repair mechanisms. Mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) leads to the accumulation of mutations across the genome, particularly in microsatellites, which over time can result in higher levels of neoantigen production, rendering the tumors susceptible to the ICI therapy (1–5).

In 2017, Le et al. demonstrated that dMMR status reliably predicted response to an ICI therapy targeting the PD-1 checkpoint protein (6). Following this discovery, ICI based on dMMR determined using either microsatellite instbility (MSI) or immunohistochemistry (IHC), gained clearance from the US Food and Drug Administation (FDA) for microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or dMMR by IHC solid tumors. This was the first time a cancer treatment was cleared based on a biomarker regardless of cancer origin (1,7). Since then, MSI-H and dMMR, have become some of the most recognized tissue agnostic biomarkers for improved survival following ICI therapy of solid tumors (6,8,9).

Continue reading “Questions Arise about TMB as a Predictive Biomarker for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy”