COVID-19 vaccine distribution efforts are underway in several countries. Recently, the Serum Institute of India celebrated the nationwide rollout of its Covishield vaccine, kicking off the country’s largest ever vaccination program. Meanwhile, many other vaccines against the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 are in either preclinical studies or clinical trials. At present, 19 vaccine candidates are in Phase 3 clinical trials, while 8 vaccines have been granted emergency use authorization (EUA) in at least one country.

In the US, mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are in distribution. Adenoviral vector vaccines authorized for distribution include Oxford/AstraZeneca AZD1222 in the UK (Covishield in India) and Gamaleya Sputnik V in Russia. A third type of vaccine consists of inactivated coronavirus particles, such as those developed by Sinopharm and Sinovac in China.

A Shot in the Arm

One thing these vaccines have in common is their route of administration. They are given in one or two doses by intramuscular injection, typically in the upper arm. While this method is common for routine vaccination, such as influenza, it can prove a deterrent in patients with needle phobia (1) or young children. Intramuscular injections often produce a local response, such as pain or swelling at the injection site. A recent report suggests that, while patients may be asymptomatic after COVID-19 vaccination, they can still harbor the SARS-2-CoV coronavirus in the upper airways and be able to transmit infection to others (2).

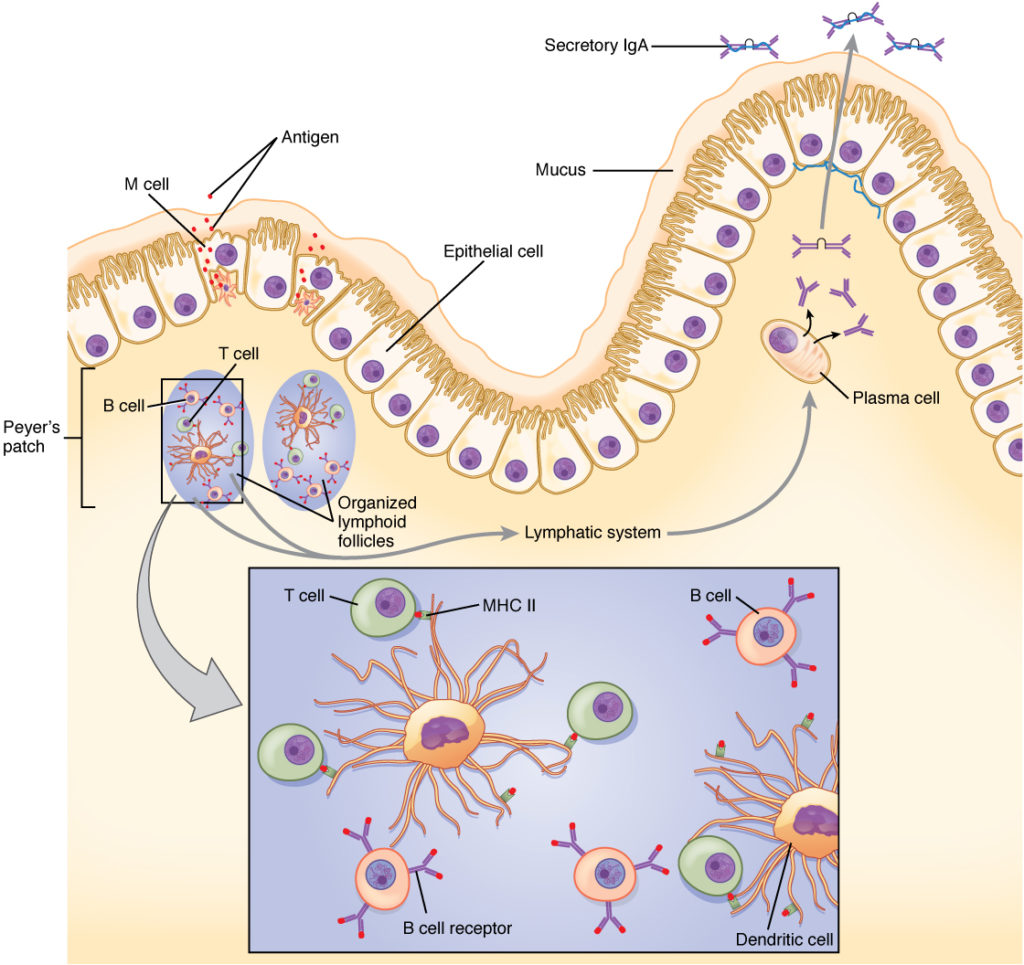

Intramuscular injections produce a systemic humoral response to a vaccine mediated by B cells, which results in the initial production of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies followed by IgG antibodies. This pathway works in concert with the T-cell immune response. However, in the cases of respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the first line of defense is the mucosal immune system, in which the response to a pathogen is mediated primarily by IgA antibodies produced by mucosal epithelial cells. In COVID-19 infection, IgA and IgG responses show a negative correlation (3); that is, a strong systemic IgG response to a vaccine may not provide an effective mucosal IgA response.

What if there was an easier way to administer an effective COVID-19 vaccine? Logically, it makes sense to attack a pathogen at the site of infection, so there has been great interest in developing intranasal COVID-19 vaccines. Besides ease of delivery, the mucosal IgA response from an intranasal vaccine can also provide effective systemic protection (4). A well-known example of an intranasal vaccine is the FluMist® Quadrivalent nasal spray from MedImmune/AstraZeneca.

Intranasal Vaccine Development

Several studies of intranasal COVID-19 vaccines are ongoing:

- An early intranasal vaccine candidate, currently in clinical trials in China, was the result of a collaborative effort among Hong Kong University, Xiamen University and several industrial partners. The vaccine is based on an attenuated influenza virus that was previously used to develop a vaccine against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

- Codagenix (Farmingdale, NY), in partnership with Serum Institute of India, has developed a single-dose, intranasal COVID-19 vaccine candidate that is currently in Phase 1 clinical trials in the UK. The vaccine contains “live-attenuated” SARS-CoV-2 particles—a weakened form of the coronavirus. The advantage of this approach is that the immune response is directed against the entire virus, and not just the spike protein (as is the case with the current mRNA and adenoviral vector vaccines). In preclinical studies, the vaccine demonstrated a broad immune response, including mucosal IgA, humoral IgG and T-cell responses.

- Altimmune (Gaithersburg, MD) has collaborated with the University of Alabama—Birmingham to develop and test its intranasal AdCOVID vaccine. This vaccine is a single-dose, replication-deficient adenoviral vector vaccine that also delivers a broad immune response and addresses safety concerns that may arise with the use of live-attenuated viral vaccines. The vaccine is being evaluated in Phase 1 clinical trials in the US.

- Other notable efforts include an intranasal, nanoparticle-based viral protein vaccine being developed by the Nanovaccine Institute at Iowa State University and Zeteo Biomedical, and an intranasal, adenoviral vector vaccine being developed at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis (5).

Lentiviral Vector Vaccine

A recent study examined both intranasal and intramuscular vaccination routes of administration in animal models (6). To address concerns with pre-existing immunity to some adenoviruses (7), the researchers developed a nonreplicative lentiviral vector vaccine that targeted the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Lentiviruses are single-stranded RNA viruses and belong to the Retroviridae family that includes HIV-1.

The researchers developed several spike protein variations and measured their ability to induce neutralizing antibodies in mice using the Luciferase Assay System. For vaccination studies, they used mice in which the human ACE2 receptor—the binding target for S protein that allows SARS-CoV-2 to enter cells—was expressed at high levels in the respiratory tract and pulmonary mucosa. This genetic modification made the mice susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, using a clinical isolate of the virus. Systemic vaccination of these mice resulted in only partial protection, despite high levels of neutralizing antibodies in serum. However, an intranasal boost induced mucosal immunity and resulted in >3 log10 decrease (>99.9%) in viral lung loads. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of intranasal vaccination against COVID-19 using a lentiviral vector vaccine, and set the stage for future clinical trials.

Summary

Intranasal vaccines offer an attractive option in the multifaceted vaccine response to COVID-19. The ease of administration and potential for fewer local reactions can increase acceptance of vaccines, especially in vulnerable populations and children. Also, unlike the current mRNA vaccines, these vaccines do not require ultracold storage and shipping temperatures. Final results from clinical trials will help demonstrate the safety and efficacy of intranasal vaccines in inducing both humoral and mucosal immunity, before they gain EUA and are available for distribution.

Learn more about viral vaccine development with our SARS-CoV-2 Research, Vaccine and Therapeutic Development resource page.

References

- McLenon, J. and Rogers, M.A.M. (2019) The fear of needles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 75(1), 30–42.

- Blier, B.S. et al. (2020) COVID-19 vaccines may not prevent nasal SARS-CoV-2 infection and asymptomatic transmission. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1–3.

- Butler, S.E. et al. (2020) Features and functions of systemic and mucosal humoral immunity among SARS-CoV-2 convalescent individuals. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.05.20168971.

- Skwarczynski, M. and Toth, I. (2020) Non-invasive mucosal vaccine delivery: advantages, challenges and the future. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 17(4), 435–7.

- Hassan, A.O. et al. (2020) A single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 183, 169–184.

- Ku, M.-W. et al. (2021) Intranasal vaccination with a lentiviral vector protects against SARS-CoV-2 in preclinical animal models. Cell Host & Microbe 29, 1–14.

- Fausther-Bovendo, H. and Kobinger, G.P. (2014) Pre-existing immunity against Ad vectors: humoral, cellular, and innate response, what’s important? Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 10, 2875–2884.

I do believe in nasal vaccine it’s the root for Covid 19 entrance but it should be the traditional old way vaccination

It’s not necessary to change what have been good and efficient for decades as body physiology remains the same

Not every one reacts well to intermuscular injections. A nasal vaccine would seem less intimidating for some one who has had a negative experience. It also seem much more practical to administer.