It is remarkable to me how quickly in vitro fertilization has gone from an experimental, controversial and prohibitively expensive procedure to becoming a mainstream option for those struggling with fertility issues. What was unheard of in my parents’ generation is nothing extraordinary among my friends who are having children.

My personal observations are supported by the CDC, which reported that 1.6% of all infants born in the U.S. in 2015 were the result of assisted reproductive technology (ART). This is a 33% increase since 2006, which can be attributed to rapid advances and refinements of the various technologies available to those seeking reproductive assistance.

It challenges the mind to imagine what reproductive technologies might be widespread when my children and their friends are adults. When experts speculate about the future of human reproduction, there always seems to be a lot of focus on provocative scenarios that portend a dystopian future, such as designer babies. What gets lost are some of the more general scientific advances that are being applied to ART in fascinating ways.

While improvements in reproductive technologies serve many, one group that remains underserved are pediatric cancer patients. As a result of treatment, these patients are often faced with impaired ovarian function that can prevent puberty and result in infertility. In vitro fertilization and ovarian transplants are currently used, but do not provide lasting solutions for all individuals.

In response to this need, researchers are working to develop an organ replacement that can provide long-term hormone function and fertility for all patients. A recent study in Nature Communications presented encouraging results in mice using bioprosthetic ovaries that may further revolutionize the field of ART.

This group of researchers used 3D printing with a gelatin ink to create a microporous scaffold that could be seeded with follicle cells from mice. One goal of the study was to mimic the compartmentalized internal structure of an ovary, allowing for ovulation (through the pores) and formation of blood vessels. After considerable optimization of the gelatin composition, printer conditions and scaffold architecture, bioprosthetic ovaries were created that met the objectives.

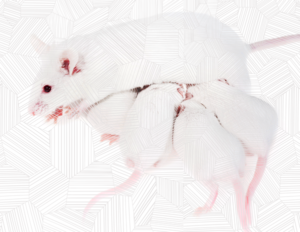

Using mice that had both ovaries surgically removed, researchers implanted either bioprosthetic ovaries (consisting of the 3D printed scaffold containing ovarian follicles) or just the scaffold structures. Once implanted, the bioprosthetic ovaries became vascularized and ovulation was initiated by hormone production from the follicles the implant was seeded with—no external manipulation was required.

Not only were the bioprosthetic ovaries functional from a physiological perspective, but they provided fertility to sterilized mice. Three of the mice that received the bioprosthetic ovaries had litters of pups, while none of the mice implanted with just the scaffolds produced any litters. Furthermore, these mice were able to lactate which indicated that the corpus luteum resulting from ovulation produced functional levels of progesterone. The pups developed normally and went on to produce their own litters.

These results support the case for conducting future preclinical studies in larger animals that could serve as the foundation for the development of human bioprosthetic ovaries. If this technology can be successfully translated to humans, it will be possible to restore both hormone function and fertility in individuals who experience impaired ovarian function. This technology may ultimately make it easier for pediatric cancer patients and their doctors to make treatment decisions, knowing that they may be able to regain reproductive function that is lost.

Wow. That’s really cool. Thank you for informing me about this bit of revolutionary science!