Last night I was helping my daughter, who is in fourth grade, with her homework. We had completed a math worksheet, a geography worksheet and had moved onto writing. For her paragraph assignment, she was supposed to write about a special place. So I began drawing the concept map that we typically use to help her organize her thoughts. She stopped me before I could get started.

“No Mom, wait,” she grabbed the pencil and paper from my hands, “I have a better idea.”

She drew five shapes on the paper.

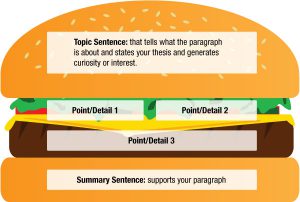

“We should write the paragraph like it’s a hamburger. The first sentence is the topic—it’s the top of the burger, tells you what is inside—it makes you hungry to read more. Next comes the juicy, meaty part. Three details—three sentences. Then the bottom bun, the summary that supports the whole paragraph. It’s the hardest to write.” She proudly sat down with her drawing and pencil.

“I LOVE that,” I exclaimed. “That’s a great way to organize a paragraph.”

“Yeah,” my husband looked up from his Suduko that he had been working on, “and the cheese goes right here.” He pointed to one of the three boxes my daughter had drawn underneath the bun.

“And the lettuce over here,” my daughter giggled.

“Well, I like mine with lettuce and tomato,” I chanted with no apologies to Jimmy Buffett, “Heinz 57 and French-fried potato..,”

“A big kosher pickle,” my daughter joined in, and the evening’s homework activities degenerated from there. (Sometimes it’s the parents who are easily distracted.)

My daughter’s hamburger graphic was new to me, but the concept wasn’t. It is a solid method for organizing a piece of writing, and it can be applied all kinds of writing—from a paragraph, to an essay, to a speech and even to a scientific article.

For instance, the five-paragraph essay simply consists of an introduction that states your thesis and names three supporting pieces of evidence. Next comes the middle part consisting of three paragraphs in which you expand on each of those points in turn, saving the strongest points for the end. You conclude with a summary that restates your three points leading a final statement of your thesis. It’s my daughter’s hamburger scheme, applied to an essay.

This same structure can be applied to a scientific paper. Traditionally scientific research papers follow the IMRaD structure: Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Materials and Methods section is unique to scientific papers, because it is the detailed description of your protocols—the part that describes what procedures you followed and materials you used, recorded for the purpose of being able to replicate results. Because it is essentially a “how to” piece, the method section is often organized along a chronology. However the remainder of the scientific paper readily lends itself to the “hamburger scheme”.

With the introduction you are setting the stage, defining the question/problem you are addressing with back ground, stating your hypothesis, and stating the main points you investigate to test that hypothesis. Introductions in scientific papers generally require more than one paragraph, but your introduction serves the same function as the bun in that hamburger diagram. It generates curiosity in your readers—gets them salivating, hungry to read more.

The Results section takes each of those experiments that you performed to test that hypothesis and discusses them individually, presenting the data and providing commentary. The results section provides the juicy, meaty content: The experimental data and empirical evidence that your readers crave.

The Discussion section is where you explain what your new results mean in the context of the larger body of work that you used to frame your hypothesis in the Introduction. Here, you are supporting your hypothesis, noting what questions are raised and any caveats, where more work is needed and future directions for inquiry.

There are fancier ways to organize your writing using techniques like comparison/contrast or pro/con structures. Chronological order works really well in some cases too. But, when I’m really stuck on a piece, and it’s not really coming together, returning to the traditional five-piece structure always helps. This structure helps me see when I have a weak point or have failed to flesh out an argument. It points out weak conclusions and reminds me that I need a beginning that tempts the reader to take a bite and savor the piece. The hamburger scheme may be taught to elementary school students, but it works for PhD-level writers as well. Try taking a bite the next time you are stymied by a writing task.

Want more science writing tips? We have a series of science writing blogs for you.

This blog updated April 4, 2024 to address broken links.

Michele Arduengo

Latest posts by Michele Arduengo (see all)

- Unlocking the Secrets of ADP-Ribosylation with Arg-C Ultra Protease, a Key Enzyme for Studying Ester-Linked Protein Modifications - November 13, 2024

- Exploring the Respiratory Virus Landscape: Pre-Pandemic Data and Pandemic Preparedness - October 29, 2024

- From Fins to Genes: DNA Barcoding Unlocks Marine Diversity Along Mozambique’s Coast - October 15, 2024