When I first learned that I had won a copy of The Where, The Why and The How in the book lottery at ScienceOnline 2013, I couldn’t believe my luck. I never win anything, at least not anything that I actually want. And I wanted a copy of this book.

When I first learned that I had won a copy of The Where, The Why and The How in the book lottery at ScienceOnline 2013, I couldn’t believe my luck. I never win anything, at least not anything that I actually want. And I wanted a copy of this book.

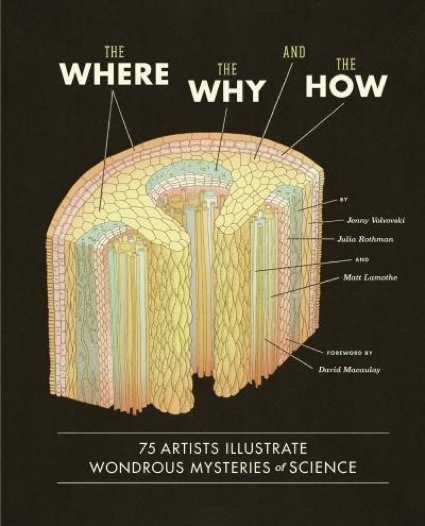

The book is beautiful to hold. The linen binding is beautiful, reminiscent of bygone days when book binding was a practiced art. The paper is thick and smooth, a tactile pleasure as you turn each page; the pages themselves sound substantial as you flip through the book. Even the smell of the book is delightful—bringing to mind the stacks of old books filling a great library, even though what you hold in your hand is a new work. The science paisley inside covers of the book are a delight to look at, comprising various science icons intricately woven into an astounding tapestry.

I was expectant when I opened the book for the first chance for a serious read.

The first essay I read, “Question 41: What Causes Autism”, disappointed almost immediately—mostly because of one sentence that seemed to give “stabilizers in certain vaccines” some scientific credibility as a potential cause of autism, when in the scientific community this explanation has been discredited. I had a hard time reading beyond that point, even though the rest of the short essay, which is engagingly written, makes a couple of good points.

I had some misgivings about a couple of other essays that I glanced over as well. Was I just picking the essays with problems? Or, was I misreading what this book is really about?

I decided to ask someone else, a colleague, a mathematician turned graphic designer what he thinks of this work. Here is our conversation:

Maciek Smuga-Otto: Knowing your reservations about the book in advance, Michele, I decided to evaluate this book as a designer, not a scientist. And I largely liked what I saw from this perspective. The secret to enjoying this book, I came to realize, is not to think of it as a popular science book, but rather as an exposition of art motivated by scientific questions.

Here’s how it works for me: I turn the pages, and see a piece of art that compels me. This motivates me to read the associated blurb, which will hopefully inform me of a couple of neat scientific ideas in the process. I then turn back to the artwork, now appreciating it with new eyes, and hopefully seeing how the science I just learned about informed the artwork.

There are several articles in the book where the above interplay between art and science works beautifully. “Do immortal creatures exist?”, “Why do we hiccup?” and “Why do primates eat plants that produce steroid mimics?” were some of my favorites, and I love the book for succeeding in these places.

Michele Arduengo: Looking at the book, not as a work of popular science, but instead as a work produced by artists who are wondering about scientific questions does make it a bit easier to relate to. I, too, loved the essay and artwork inspired by the question “Do immortal creatures exist?” (particularly after I took off my science editor hat). I love the way the artist not only interpreted the essay graphically but also brought in one of my favorite pieces of literature.

The art for “Why do primates eat plants that produce steroid mimics?” did stop me–it is beautiful. In that instance, the art stops me and the essay lends interpretation to the artwork. These pieces work really well as “artist explorations of a topic” (from David Macaulay’s foreword to the book).

Perhaps the “unorthodox” labeling of the cover image and the foreword to the book are cues that this is a book of artist explorations–not science essays with illustrations, and I simply missed them.

That said, I still have some concerns about a few of the essays and artwork that seem to be trying to be more definitive (by length/detail) or trying to address “hot button” scientific questions. They simply are not definitive, and there is a danger in them being interpreted as such.

MSO: Agreed. While the book worked for me in places, it fell short of its potential in others. Sometimes, as you pointed out, it would tackle questions that were either way too big in scope, resulting in uninformative blurbs (“What happened before the big bang?”), too much information (“What is the God Particle?”) or way too sensitive for the minimal treatment they got (“Is homosexuality innate?”).

The more I think about it, the more I come to realize that the book works best when it’s not taking itself too seriously: David Macaulay’s illustration “Canaletto Changes a Lightbulb” is the perfect introduction that sets the right tone for what follows (Macaulay has been a hero of mine for a long time, injecting genuine humor into technical, scientific and educational illustrations since… forever). Unfortunately, trying to tackle “big” scientific questions, or featuring over-long, detailed answers (TL;DR) or taking on a controversy-riddled subject takes all the tongue-in-cheek out of it.

MA: Okay, you’ve convinced me. Take off my science editor hat and enjoy the cool pieces of artwork and their short interpretive bits. Particularly enjoyable were: “What does ‘chickadee’ mean to a chickadee?”, “Why do pigeons bob their heads when they walk?” (the art for this one really drew me into the question), and “Do squirrels remember where they bury their nuts?”

What were some of your other favorites? And, would you recommend this book to others?

MSO: One more quick thought before I jump in with my favorites. Because the book features such a wide variety of art styles, almost anybody will likely find something there that they click with, and will want to find out more about. So yes, I’d recommend this as a great coffee table book. Just make sure your scientist hat is firmly put away before opening the book.

Now for some of my other favorite artwork that we didn’t get to above: Dark matter (p. 15), Earth hum (p. 37), Plate tectonics (p. 39), Earthquakes (p. 41), Rogue waves (p. 47) – I love that little schooner being tossed like that, Ice age (p. 65), Sleep (p. 81), Depression (p. 91), Placebos (p. 95), Phermones (p. 99), Genome junk (p. 153), and Cell talk (p. 157). These are all pictures that compel me to read the associated sciency blurb. Sometimes the reading is scientifically interesting, sometimes not so much. But in all these cases it explains the motive for the artwork just a little bit more, and that makes it all worthwhile for me.

Thanks so much for loaning the book to me, and for suggesting this conversation. It’s been great fun!

MA: Yes, it has been fun. Thanks for opening my eyes to a different way of viewing the book. I would recommend the book too, with the same understanding: put away the scientist hat first.

Michele Arduengo

Latest posts by Michele Arduengo (see all)

- An Unexpected Role for RNA Methylation in Mitosis Leads to New Understanding of Neurodevelopmental Disorders - March 27, 2025

- Unlocking the Secrets of ADP-Ribosylation with Arg-C Ultra Protease, a Key Enzyme for Studying Ester-Linked Protein Modifications - November 13, 2024

- Exploring the Respiratory Virus Landscape: Pre-Pandemic Data and Pandemic Preparedness - October 29, 2024