New information has surfaced about this story, and we encourage you to read our updated blog from July 2024 (linked) for the latest on this story.

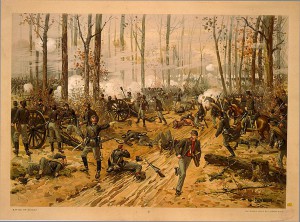

If battlegrounds could speak they would have many stories to tell. In some cases the microbes found in those soils have lived on to separate fact from fiction. One such story has its origins in the Battle of Shiloh, which went down in history as one of the bloodiest battles fought during the American Civil War. As the soldiers lay mortally wounded on the cold, hard grounds of Shiloh waiting for medical aid, they noticed a very strange phenomenon. Some of the wounds actually appeared to be glowing in the dark casting a faint light into the darkness of the battlefield. And the legend goes that soldiers with the glowing wounds had a better chance at survival and recovery from infections than their fellow brothers-in-arms whose wounds were not similarly luminescent. The seemingly protective effect of the mysterious light earned it the moniker “Angel’s Glow.”

Fast forward to the 21st century.

A high school student, named Bill Martin, was visiting the battlefield in Shiloh in the year 2001 and was intrigued by this story. Luckily for him, his mom was a microbiologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service. He was familiar with his mom’s work on luminescent bacteria that lived in the soil. They made the connection that the glowing wounds could in fact have been caused by the same microorganism that his mom was studying; Photorhabdus luminescens. Being a scientist herself, she encouraged her son to investigate this further. What he uncovered was a remarkable explanation behind a story that was long regarded to be little more than a legend.1

Martin and his friend, Jon Curtis, probed both the bacteria and the conditions during the Battle of Shiloh. They discovered that Photorhabdus luminescens, the bacteria that Martin’s mom studied and the one he thought might have something to do with the glowing wounds, shared a symbiotic life cycle with parasitic worms called nematodes. Nematodes are predators that burrow into insect larvae residing in the soil or on plant surfaces and take up residence in their blood vessels. There, the worms regurgitate the P. luminescens bacteria living inside their guts producing a soft blue light. The bacteria then release a cocktail of toxins that kill the insect host and suppress the growth of other microorganisms that might decompose the larval corpse. This allows P. luminescens and their nematode partner to feast on their prey’s carcass uninterrupted. When they are done devouring the insect host, the bacteria re-colonize the nematode’s guts and piggy-back with the worm as it bursts forth from the corpse in search of a new host. And what’s more – the glow emanated by the parasitized insect is thought to lure in other insect prey.2,3

Was it possible that the chemicals released by P. luminescens were responsible for helping the soldiers survive their horrific wounds? Based on the evidence that P. luminescens was present at Shiloh and the reports of the strange glow from the soldier wounds, Martin and Curtis hypothesized that the glowing bacteria invaded the soldiers’ wounds when nematodes preyed on insect larva who are naturally attracted to such injuries. The resulting infestation could have wiped out any competing, pathogenic bacteria found in wounds besides bathing them in a surreal glow.

The only caveat with the hypothesis was that P. luminescens cannot survive at human body temperatures. The young scientists had to come up with a novel explanation to fit this piece of the puzzle. The clue lay in the harsh conditions of the battlefield itself. The battle was fought in early April when temperatures were low and the grounds were wet with rain. The injured soldiers were left to the elements of nature and suffered from hypothermia. This would provide a perfect environment for P. luminescens to overtake and kill off harmful bacteria. Then, when the soldiers were transported to a warmer environment, their bodies would have naturally killed off the bug. For once, hypothermia was a good thing.

Often, a bacterial infection in an open wound would herald a fatal outcome. But this was an instance where the right bacterium at the right time was actually instrumental in saving lives. The soldiers at Shiloh should have been thanking their microbial buddies. But who knew back then that angels came in microscopic sizes? As for Martin and Curtis, they went on to win first place in team competition at the 2001 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. Personally, I used this story as an example to my own children of how simple curiosity leads to solving bigger problems.

New information has surfaced about this story, and we encourage you to read our updated blog from July 2024 (linked) for the latest on this story.

References:

- http://sciencenetlinks.com/science-news/science-updates/glowing-wounds/

- Sharma S. et al. (2002). The lumicins: novel bacteriocins from Photorhabdus luminescens with similarity to the uropathogenic-specific protein (USP) from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 214, 241-9.

- https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Photorhabdus_luminescens

Radhika Ganeshan

Latest posts by Radhika Ganeshan (see all)

- T-Vector Cloning: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions - February 19, 2016

- Beating the Odds of Cancer: Not Just a Tall Tale - October 12, 2015

- Removing Cancer’s Cloak of Invisibility - April 20, 2015